Introduction

General issues of mobility in Roman times to the east coast of the Adriatic have only recently attracted greater scholarly interest.1 The paper examines the identity of the people who settled permanently in Histria during the Imperial Period, their origins, what prompted them to move, and how they fared after settling, and traces the existence of seasonal, temporary migrants (Map 1).2 The Roman colonisation of Histria began with the foundation of Roman colonies Pola, Tergeste and Parentium, from Caesar’s to Tiberius’ period. During the Imperial Period, a significant number of migrants settled in various parts of Histria, in cities, in villas, in colonial agri, and in the territories of indigenous communities. Most immigrants were slaves who did not come of their own free will but as movable property and an object of trade. For the purpose of this paper, slaves are excluded and the focus rests on tracing through the epigraphic record free individuals, both freeborn and freedmen, who migrated voluntarily in search of a better life and trade earnings, veterans, or others who found refuge in Histria from troubles in their homeland. I say ‘voluntarily’ even for curatores and active soldiers. They were free individuals who came to Histria under orders; their duty was a result of their free will and choice, unlike the slaves.

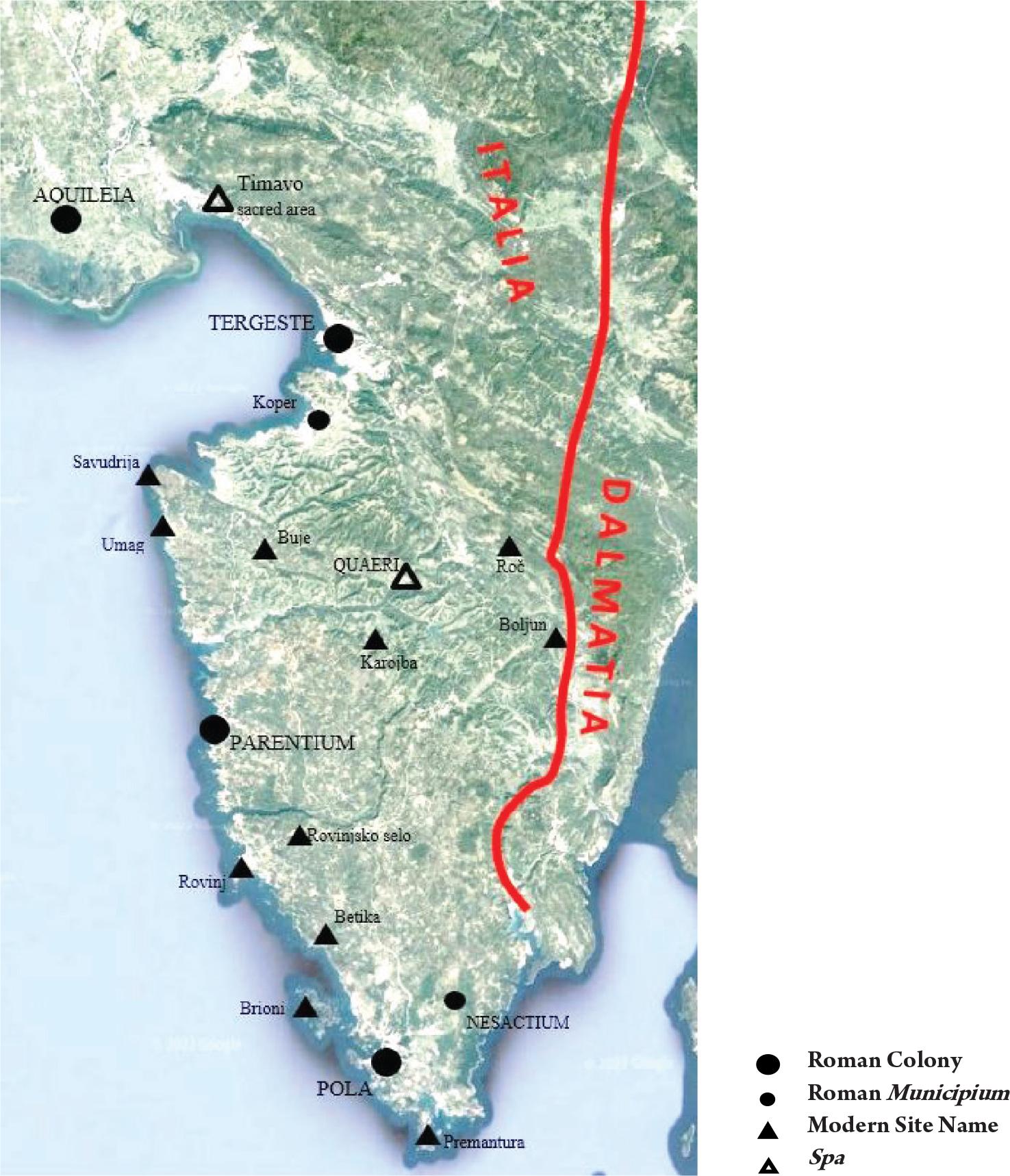

Map 1: Histria and nearby areas. Base map sourced from Google Maps; graphics created by the author.

The study spans the Roman Imperial Period, from Augustus’ rise in 27 BCE till the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE; the epigraphic record from the first and second century CE is much richer and, consequently, over-represented in this study. The granting of Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Roman Empire (Constitutio Antoniniana, 212 CE)3 may have mitigated some reasons for resettlement, but it did not stop migration. Indeed, of all the inscriptions examined in the study, only one sarcophagus lid bearing a Greek inscription (EDR 142385) is dated safely after the Constitutio Antoniniana. This rarity could be interpreted as an indication of less frequent migration to Histria after 212, but caution is advised because the overall number of stone inscriptions in Histria sharply decreases from the beginning of the third century.4 Thenceforth, inscriptions are almost exclusively preserved on sarcophagi, which only the wealthiest could afford. Therefore, the absence of data on migrants after 212 CE is not a clear indication of a real decrease in their number.

Inscriptions attest to various types of migration in Histria: seasonal, temporary, and permanent. Different kinds of foreigners to the land are attested: municipal aristocracy, magistrates, city patrons, Augustals, soldiers, praetorians, veterans, high-ranking military commanders, merchants, pilgrims, even a deposed barbarian king with his family. Their motives for coming to Histria were very different: some came of their own free will; others were descendants of slaves; some officials came to fulfill their administrative duties; veterans and a deposed barbarian king were settled in Histria by the decision of the authorities. Some died during a temporary stay in Histria, away from home. Many settled permanently or came seasonally for work, trade, earnings, to harvest the income of estates distant from their permanent residence and enjoy leisure, while others came with a specific purpose motivated by personal or religious reasons, to visit the shrine at the source of the Timavo river or receive treatment at the local spa.

Migration to Histria was purely individual. For the purpose of this paper, the migration of the individuals whose names appear on stone is considered as individual migration, as opposed to group migration. That is with the understanding that those private individuals may have been accompanied by family members, whose presence we cannot detect in the epigraphic record. Historical sources record the looting of the Pannonians and Noricans during the reign of Augustus, but this episode left no archaeological traces of a permanent settlement in Histria.5 Group immigration is not attested in historical sources before the fall of the Roman Empire and the ensuing great migration of the Ostrogoths, which left a clear archaeological trace in Histria.6

Epigraphic Data on Migrants to Histria

Greek inscriptions in Histria are overwhelmingly outnumbered by Latin ones, yet it is impossible to ascertain, based on the existing epigraphic evidence, whether the descendants of the migrants in Histria spoke and wrote Greek. Quite characteristically, every Greek inscription preserved is linked to a migrant from the Eastern provinces. Together, they provide valuable information about the free Greeks settlers in Histria (Table 1).7 Most, but not all, had a Greek cognomen, as expected. The name Ληουίτος (n. 1) is of Jewish origin.8 Other Greek inscriptions from Histria were paid and erected by slaves: Γλύκερα,9 Σιλουέστερ,10 Σιλβάνη,11 and the couple Θησεύς Όνησίμου and Άρτεμις Ποσιδωνιου.12 The funerary monument of Άμμώνιος from Alexandria13 and the inscription of spouses Όρκηβία Πῶλα Ποπλίου and Γαϊος Τορπίλιος from Rome were bought at antiques markets;14 their uncertain provenance cannot safely place them in the colony of Tergeste as proposed in the corpus IIt X/4. While persons for whom both family and personal names are scribed were free citizens who migrated to Histria of their own free will, those attested with only their personal name were, in most cases, slaves forcibly brought to the region,15 except Εύσέβιος and Εύσεβία (n. 4):16 their names were probably added to an older sarcophagus in Late Antiquity, when the family name had lost its significance as an indicator of citizenship and much of the citizens came to have one, personal name.17 Latin inscriptions indicating the place of origin or foreign tribe of a person are, as expected, much more numerous than Greek ones (Table 2).

Table 1: Greek Inscriptions from Histria Bearing Names of Roman Citizens

| No | Publication | Names Inscribed | Origin | Type of Monument |

Material | Site | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | IIt X/1 212 = EDR 136480 | Αύρήλιος Πρόκλος Ληουίτου | Eastern Mediterranean, Syrian provinces? | Sarcophagus | Unknown | Pola | 161-300 CE |

| 2 | IIt X/1 26 = EDR 135210 |

Κλαυδία Καλλικράτεια, Κορνήλιος Διαδούμενος | Eastern Mediterranean | Votive altar | Limestone | Pola | 100-200 CE |

| 3 | IIt X/1 588 = EDR 138888 | Pουφία Xρυσόπολις | Eastern Mediterranean | Funerary altar | Marble | Pola, Premantura | 100-200 CE |

| 4 | IIt X/1 166 = EDR 136263 | Εύσέβιος, Εύσεβία | Eastern Mediterranean | Sarcophagus, bilingual (Greek inscription added at a later date) | Unknown | Pola | ? |

| 5 | Šašel, Marušić 1984, 313, no. 40 = EDR 142385 | [---]νος | Eastern Mediterranean | Sarcophagus lid | Limestone | Brioni | 300-500 CE |

Table 2: Latin Inscriptions Bearing Names of Resettled Citizens and their Descendants in Histria

| No | Publication | Inscribed Names | Origin | Type of Monument |

Material | Site | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | IIt X/1 78 = EDCS-04200051 | P. Aelius P. f. Camil. Octavus aed. IIvir i. d. Polae | Ravenna? Italy Regio VIII | Sarcophagus | Limestone | Pola | 170-200 CE |

| 7 | IIt X/1 153 = EDCS-04200032 | P. Aelius Rasparag[a]nus, rex Roxo[la] noru[m] | Sarmatian Barbaricum | Uncertain (possibly sarcophagus) | Limestone | Pola, Uljanik island | 120-160 CE |

| 8 | IIt X/1 154 = EDCS-04200033 | P. Aelius Peregrinus, reg[is] Sarmatarum Rasparagani f. | Sarmatian Barbaricum | Uncertain type of funerary monument | Limestone | Pola, Uljanik island | 140-180 CE |

| 9 | IIt X/1 199 = EDCS-04300083 | C. Antonius Zosimianus signo Dalmatius | Dalmatia | Stele | Limestone | Pola | 100-300 CE |

| 10 | IIt X/1 105 = EDCS-04200066 | Sex. Apuleius Sex. liber. Apollonius VIvir aug. Terg(este) et Pol(ae) | Tergeste or Pola? Italy Regio X | Unknown | Unknown | Pola | 70-200 CE |

| 11 | IIt X/1 80 = EDCS-04200053 | M. Aurelius Felix d[ec(urio)] Cremonensium, qua[e]stor pecuniae publicae, aedilis P[o]l(ae), [I]Ivir iure di[c. q]q. | Cremona, Italy Regio X | Unknown | Unknown | Pola | 150-250 CE |

| 12 | IIt X/1 244 = EDCS-04200229 | Calvius Fidentinus | Fidentia, Italy Regio VIII | Tombstone | Limestone | Pola | 150-300 CE |

| 13 | IIt X/1 163 = EDCS-04300072 | Q. Catusius Sever[ianus, civis] Gallus, negotiator [vestiarius] | Alpine region | Sarcophagus | Limestone | Pola | 170-200 CE |

| 14 | IIt X/1 74 = EDCS-04300023 | Sex. Caulinius Syrus, father of the veteran of coh. VIIII pr. | Syria | Funerary altar | Limestone | Pola | 40-70 CE |

| 15 | IIt X/1 83 = EDCS-04200055 | Iulia Fortunata, honoured by ordo Aquilensium | Aquileia or Pola? Italy Regio X | Unknown | Unknown | Pola | 100-300 CE? |

| 16 | IIt X/1 171 = EDCS-04200181 | M. Postumius L. f. Pub(lilia) Postumus Veronensis | Verona, Italy Regio X | Stele | Limestone | Pola | 1-100 CE |

| 17 | IIt X/1 66 = EDCS-04200035 | C. Precius Felix Neapolitanus | Neapolis, Italy Regio I | Statue base | Unknown | Pola | 50-75 CE |

| 18 | IIt X/1 119 = EDCS-04200070 | L. Satonius Trophimus, VIvir Aquileiae | Aquileia, Italy Regio X | Funerary altar | Limestone | Pola | 1-100 CE |

| 19 | IIt X/1 67 = EDCS-04300021 |

C. Set[tidius] C. f. Pup(inia) Fir[mus], praef. coho[r.] IIII Thrac. Sy[r.], trib. mil. leg. V Maced., q. urb. |

Tergeste (?), Italy Regio X | Statue base? | Limestone | Pola | 1-100 CE |

| 20 | AÉ 1984 426 = EDCS-08400258 |

[T. Settidius C. f. P]upin(ia) Firm[us ---cianus], cos., [praef. a]liment., curat. [viae, leg. leg. VI Fer]ratae et VII CPF, [leg. prov. Cappadociae Galatiae Lyc] aoniae, le[g. prov. ---] |

Pola, Italy Regio X | Tombstone | Limestone | Pola, Betika | 115-150 CE |

| 21 | IIt X/1 167 = EDCS-04200178 |

[---]us Dosae fil. ex Syria Palaestina (domo) Neapoli | Neapolis, Syria Palaestina | Sarcophagus | Limestone | Pola | 150-230 CE |

| 22 | IIt X/1 111 = EDCS-04300038 |

[---] L. l. Fabr[us sevir a]ug. Te[rgeste et Polae?] |

Tergeste or Pola? Italy Regio X |

Tombstone | Limestone | Pola | 1-100 CE |

| 23 | IIt X/1 28 = EDCS-04300011 = EDR135217 |

[--- a]b Efeso natus |

Ephesus, Asia | Tombstone | Limestone | Pola | 1-100 CE |

| 24 | IIt X/1 176 = EDCS-04200186 |

[---] Tergeste | Tergeste, Italy Regio X | Tombstone | Unknown | Pola | |

| 25 | IIt X/1 644 = EDCS-05401423 |

L. Campanius L. f. Pol(lia) Verecundus, [ve]teran. leg. IIII Scy[th(icae) si]gnifer, (centurio) c(o)ho. [C]isipadensium | Italy Regio VIII | Stele | Limestone | Pola, Karojba near Rovinj |

1-100 CE |

| 26 | CIL V 8667 = EDCS-05401465 |

Q. Decius Q. f. Cl(audia) Mettius Sabinianus, curat(or) r(ei) p(ublicae) Polens(ium) | Concordia, Italy Regio X | Statue base | Limestone | Concordia | 130-170 CE |

| 27 | IIt X/1 675 = EDCS-04200004 |

C. Furius C. f. Arn(ensis) Gemellus, mil. coh. IIII pr(aetoriae) |

Italy, Regiones IV, VI-VIII? |

Architectural stele with pilasters and gable | Limestone | Nesactium, Valtura | 1-50 CE |

| 28 | IIt X/2 253 = EDCS-04400182 |

P. [Te]dius P. f. Pup(inia) Valens (domo) Terg(este), signifer leg. IIII F(laviae) F(elicis) |

Tergeste, Italy Regio X | Architectural stele with gable | Limestone | Parentium, Karojba | 75-100 CE |

| 29 | IIt X/3 31 = EDCS-04200572 |

C. Titius C. f. Volt(ilia) (domo) Vienna, veteranus leg. XV Apol(linaris) | Vienna, Gallia Narbonensis | Tombstone | Limestone | Koper, Pomjan | 15 BCE - 15 CE |

| 30 | IIt X/3 42 = EDCS-04200565 |

Q. Ragonius L. f. Rom(ilia), L. Ragonius L. f. Rom(ilia), brothers |

Italy Regiones I-III, X? |

Tombstone | Limestone | Savudrija, Frančeskija | 1-50 CE |

| 31 | IIt X/3 46 = EDCS-12300338 |

L. Vespennius L. fil. Pol(lia) Proculus (domo) Faventia, coh. X urb. |

Faventia, Italy Regio VIII | Military diploma | Bronze | Umag, Ježi | 194 CE |

| 32 | IIt X/3 200 = EDCS-04200411 |

C. Valerius Priscus, vestiarius Aquileiensis | Aquileia, Italy Regio X | Funerary altar | Limestone | Boljun | 75-125 CE |

| 33 | IIt X/4 49 = EDCS-04200630 |

P. C[lodi]us Quirinalis, miles leg. XV Apol(linaris), father of P. Palpellius P. f. Maec(ia) Clodius Quirinalis |

Neapolis, Italy Regio I |

Stele | Limestone | Tergeste | 25-50 CE |

| 34 | IIt X/4 52 = EDCS-04200631 |

T. Dom[i]tius Gracilis, nat(ione) Ditio, miles | Ditiones, Dalmatia |

Stele | Limestone | Tergeste | 50-75 CE |

| 35 | IIt X/4 80 = EDCS-04200646 |

P. M[---] Pollio, [de]cur(io) Polae | Pola, Italy Regio X | Unknown | Unknown | Tergeste | 1-200 CE |

| 36 | IIt X/4 139 = EDCS-04200654 |

L. Mussius Sal(vi) f. Pol(lia), Fano Fort(unae) natus | Fanum Fortunae, Italy Regio VI | Tombstone | Limestone | Tergeste | 25 BCE - 25 CE |

| 37 | IIt X/4 32 = EDCS-04200622 |

P. Palpellius P. f. Maec(ia) Clodius Quirinalis, p(rimus) p(ilus) leg. XX, trib. milit. leg. VII CPF, proc. Aug., praef. Classis |

Neapolis, Italy Regio I | Architrave | Limestone | Tergeste | 50-56 CE |

| 38 | AÉ 1977 314 = EDCS-10900079 |

C. Velitius M. f. Lemo(nia) (domo) Bononia, miles leg. XX |

Bononia, Italy Regio VIII | Stele | Limestone | Tergeste | 15 BCE - 10 CE |

| 39 | IIt X/4 322 = EDCS-04600144 |

C. Curius Quintinianus Opiterginus | Opitergium, Italy Regio X | Votive altar | Limestone | Sacred area of the sources of the Timavo river |

100-200 CE |

| 40 | IIt X/4 325 = EDCS-04200800 |

[T.] Auconius Optatus, eq(ues) R(omanus), dec(urio) et IIvir Cl(audiae) Ag(uonti) | Aguntum, Noricum |

Votive altar | Limestone | Sacred area of the sources of the Timavo river |

150-200 CE |

A large database comprising 1942 Latin and 10 Greek inscriptions from Histria provides information on 48 Roman citizens who were or could have been migrants from other parts of the Roman Empire (not counting patrons). As far as any fragmentary epigraphic record can be trusted to reflect general trends, it follows that migrant Roman citizens appear on 2.45% of inscriptions from the region. The analysis of inscriptions shows that the number of migrants was at least as high or higher in the colonies of Pola and Tergeste than in other parts of Histria: the percentages of inscriptions mentioning migrant Roman citizens in those two parts are 2.8% and 1.9%, respectively. Apparently, in relation to the total population, the number of migrants was quite small,18 yet even smaller number of migrants are documented in the rural hinterland, where they resided because of their occupation or settled as veterans. Still, the percentage of inscriptions of migrant Roman citizens in inner northern Histria (2.7%) corresponds to that in Pola. In certain cases, it is possible to distinguish permanently settled migrants from temporary visitors to Histria. Temporary visitors include at least pilgrims and guests of important religious and health centres, such as the spa and sacred sources of the river Timavo between Tergeste and Aquileia (Map 1). Earlier research placed the source of the river in the area of Tergeste,19 but now scholars agree that it was located in the territory of Aquileia, as Pliny notes.20 As a frontier area of special religious significance, it is included in this analysis of migrations in Roman Histria and Tergeste. Visitors from Opitergium in Veneto (n. 39) and Aguntum in Noricum (n. 40) left votive altars there (Map 2).

Map 2: Origins of private migrants to Histria from Italy, Gaul, Noricum, and Dalmatia. Source map: http://www.vidiani.com/maps/maps_of_europe/large_detailed_satellite_map_of_europe.jpg (CC-BY SA 3.0); graphics drawn by the author.

Magistrates, Decurions, and Augustals

Among the resettled individuals were members of the senatorial and equestrian orders and the municipal aristocracy. T. Settidius C. f. Pupin(ia) Firmus (n. 20), probably consul suffectus in 112 CE, was a member of an important senatorial family that originated in Tergeste and settled in Pola in the first century CE.21 They held estates in Betika and Stancija Durin near Muntić, close to Nesactium. C. Settidius C. f. Pup. Firmus (n. 19), quaestor urbanus honoured with a statue base in Pola, was one of his ancestors, probably his father.22 Senators who acquired the property in the territory of another municipality could transfer their registration from the old tribe to their new one.23 The Settidii had the legal right to change from their original Pupinia tribe belonging to the colony of Tergeste to the Velina tribe, the official tribe of the colony of Pola, but they did not do so for generations. Although assigned to a foreign tribe, members of the Settidii family after the quaestor urbanus were not newcomers, but permanent citizens of Pola.

Chief municipal magistrates originally from Rome are attested in Histria already at the end of the Republic; L. Cassius C f. Longinus, brother of Caesar’s murderer, and L. Calpurnius L. f. Piso, consul in 58 BCE and father-in-law of Julius Caesar, were appointed as the first duumvirs of the newly founded Roman colony of Pola as adsignatores, special trusted commissioners sent by the supreme founder (constitutor) Julius Caesar.24 They probably visited Pola occasionally to fulfill their administrative duties, but did not stay permanently. Permanently settled magistrates of foreign origin appear later in the epigraphic record, in the Imperial Period. Two magistrates of foreign origin held the highest administrative positions in Pola; one (P. Aelius P. f. Camil. Octavus) is revealed by his tribe, the other (M. Aurelius Felix) states in his funerary monument that before coming to Pola he was a member of the Cremona city council. P. Aelius P. f. Camil. Octavus (n. 6), aedilis and duovir of Pola, was buried in a sarcophagus dated to the last third of the second century CE.25 Of the possible settlements in northeastern Italy that could have been his hometown, Camilia was the tribe of Atria in Regio X and of Ravenna in Regio VIII.26 Aelii are not epigraphically attested in Atria, but in Ravenna, they appear in fifteen inscriptions. Therefore, Aelius Octavus probably came from Ravenna to Pola. M. Aurelius Felix (n. 11) began his career in Cremona as a decurion, then moved to Pola, became quaestor, aedilis and finally duovir in the second half of the second or first half of the third century CE.27 Cremona was assigned to the Aniensis tribe.28 Both magistrates bear the imperial personal and family name, which may indicate that they are descendants of slaves and freedmen in the imperial service.29

Other decurions migrating in the region are recorded in the inscriptions. P. M[---] Pollio (n. 35), decurion of Pola, appears in a fragmentary inscription from Tergeste. The stone records a relocation of a decurion within Roman Histria, one who did not necessarily enjoy a successful career in Tergeste. Auconius Optatus (n. 40), an equestrian and probably a wealthy merchant, served as a decurion and duovir in Aguntum in the province of Noricum.30 He briefly visited the sacred area of the source of the river Timavo with spa and dedicated an altar to Spes Augusta for the health of his son.

P. Palpellius P. f. Maec(ia) Clodius Quirinalis (n. 37) is one of the most famous migrants in Histria who did have a successful career thanks to the senatorial family of the Palpellii from Pola - one member of the family (unknown to us) adopted him and offered ample financial support.31 His tribe, Maecia, to which the cities of Lanuvium, Neapolis, Brundisium, Paestum, Rhegium, Hatria, and Libarna were assigned, was particularly common in the central and southern Italy.32 Neapolis in Campania is assumed as his city of origin, i.e. the city of his father, P. Clodius Quirinalis (n. 33), soldier of the Legion XV Apollinaris, buried in Tergeste.33 Palpellius Clodius Quirinalis gained wealth as the owner of a ceramic workshop.34 Another Neapolitan, C. Precius Felix (n. 17), came from Neapolis to Pola following his benefactor, senator Sex. Palpellius Hister.35 It seems that the wealthy senatorial family of the Palpellii attracted a number of Neapolitans from Campania to Histria and supported their careers.

For wealthy freedmen, the path to social prestige led through the college of the seviri Augustales, which administered the imperial cult. Migrants also entered this social group, positioned according to the relative importance between city officials and citizens. L. Satonius Trophimus (n. 18), sevir of Aquileia in the first century CE, erected a funerary monument to his prematurely deceased slave in Pola.36 This shows that after the end of the service, he moved from Aquileia to Pola. Sex. Apuleius Sex. liber. Apollonius (n. 10) and a certain Fabrus, freedman of Lucius (n. 22), were seviri Augustales in two Histrian cities a little more than 100 kilometres apart, Tergeste and Pola, in the first and second centuries CE, but it is impossible to determine from which of the two cities each one came from.37 Wealthy individuals, freeborn and freedmen, owned lands and properties in more than one place, but it is impossible to tell whether this was a direct outcome of their holding offices in more than one place, or of simple purchases in their new residence.

Ethnic Appellations and Identifications; Craftsmen and Traders

Certain citizens proudly declared their origin or ethnicity in inscriptions, like an individual (the name is not preserved) born in Ephesus (n. 23); Precius Felix (n. 17), from Neapolis in Campania; Catusius Severianus (n. 13), a Gaul; a son of Dosa (n. 21; his name is not preserved), from Neapolis in Syria Palaestina; Postumius Postumus (n. 16), from Verona; Calvius (n. 12), from Fidentia; Valerius Priscus (n. 32), from Aquileia; soldier Domitius Gracilis (n. 34), a Ditio;38 Mussius of the Pollia tribe (n. 36), born in Fanum Fortunae;39 Curius Quintinianus (n. 39), from Opitergium;40 and an unnamed person from Tergeste buried in Pola (n. 24).41 Some citizens are recognisable as migrants or descendants of migrants by their family name of ethnic or geographic origin (Table 3). In cases where the family name appears to be derived from the name of a remote region or people, there is a serious possibility that they were not first-generation migrants. These are the cases of Maxuma Umbria (n. 41),42 Praetorian Gallius Silvester (n. 44), and collegium members Gallius Felix, Lopsius Clymenus, and Lopsius Aprio (n. 45).43 The name of the family of Lopsii name may have been derived from Lopsica, a Liburnian municipium with Italian right (ius Italicum).44 The cognomen as a personal name indicates a newcomer much more clearly when it emphasises origins from distant lands, as in the cases of Caulinius Syrus (n. 14), Lorentius Tesifon (n. 42), Plexina Etruscus (n. 43),45 and Voltidius Gazaeus (n. 47).46 In the case of Dalmatius (n. 9), a nickname (signum) could indicate geographical or ethnic origin.47

Table 3: Inscriptions of Free-Born Citizens with a Foreign Ethnic or Regional Name

| No | Publication | Inscribed Names | Origin | Type of Monument | Material | Site | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | IIt X/1 651 = EDCS-04300314 | Maxuma Umbria | Italy Regio VI | Votive altar | Limestone | Pola, Rovinjsko Selo | 50 BCE - 20 CE |

| 42 | IIt X/3 20 = EDCS-04200587 | C. Lorentius Tesifon | Ctesiphon, Mesopotamia | Sarcophagus | Limestone | Koper | 200-300 CE |

| 43 | IIt X/3 49 = EDCS-04200562 | L. Plexina Etruscus | Italy Regio VII | Stele | Sandstone | Umag, Šeget | 50-100 CE |

| 44 | IIt X/3 124 = EDCS-04200517 | L. Gallius Silvester, mil(es) c(o)hort(is) II praet(oriae) | Northern Italy, Alpine region? | Funerary altar | Limestone | Roč, St. Maur | 75-100 CE |

| 45 | IIt X/4 95 = EDCS-04200667 | L. Gallius Felix, L. Lopsius Clymenus, L. Lopsius Aprio, collegium members | Northern Italy, Alpine region? Lopsica, Dalmatia? |

Tombstone of association members | Limestone | Tergeste | 1-50 CE |

| 46 | IIt X/4 156 = EDCS-04200731 | P. [Trosius] Peregrinus, son of P. Trosius Severus | - | Funerary altar | Limestone | Tergeste | 1-75 CE |

| 47 | IIt X/4 170 = EDCS-04200736 | C. Voltidius Gazaeus | Judaea? | Portrait stele | Limestone | Tergeste | 1-50 CE |

Among migrants without ties to the administration or the military, clothing merchants stand out and are, in fact, the only attested profession relating to crafts and trade. The monument of Valerius Priscus (n. 32), vestiarius Aquileiensis, was found in Boljun, the hilly hinterland of northern Istria with vast pastures and animal husbandry.48 In his case, migration from Aquileia (where a strong association of clothing merchants is attested)49 via Tergeste to the Učka mountain pastures was seasonal, motivated by the purchase of sheep wool during the shearing season.

A migration flow existed between the cities or commercial farms and mountain regions across Italy, causing an annual cycle of population expansion and contraction.50 Q. Catusius Severianus (n. 13), a Gaul, earned his living as a clothing merchant in Pola.51 His sarcophagus of extremely simplified architectonic type belongs to a subgroup of sarcophagi designed and manufactured initially of red Valpolicella limestone in the vicinity of Verona, during the second half of the second century CE.52 It follows that Catusius Severianus, possibly born in Gaul, moved with his family to Pola from Verona, where he kept trade ties and acquired a taste for this particular subtype of sarcophagus. Since his sarcophagus is made of white Istrian and not red Valpolicella limestone, it can be assumed that there was an interconnected group of settlers from Verona in Pola that included stonemasons.

The family of the Ragonii (n. 30) from Savudrija was assigned to the Romilia tribe, the oldest among the rural tribes, particularly widespread in Latium, the surroundings of Rome, and the city of Sora,53 with a presence also in southern Italy, Apulia, and Lucania.54 Judging by the territorial concentration of the name Ragonii, it can be concluded that they originated from Ostia.55 Ateste in northern Italy was also assigned to the Romilia tribe, but no presence of the Ragonii is attested there.56 The family may have been involved in the production of ceramic building materials, if they were the owners of the brick stamp Q. RIINI Λ, attested in northwestern Istria only.57

The funerary monument of Calvius Fidentinus (n. 12) can be dated to the second half of the second or third century CE, as the wording of the inscription suggests. Fidentia, the city of his origin, was located between Parma and Placentia in Aemilia, in the Augustan Regio VIII (Map 2).58

A Palestinian from Neapolis, mod. Nablus (Map 3), the son of a certain Dosa (n. 21), came to Pola from Syria Palaestina in the late second century CE, as evidenced by the fragmentary inscription found in second use, and thought to have been a sarcophagus pedestal initially.59 Dosis is a Jewish name recorded in Palestine.60 The use of the name Syria Palaestina, attested between 135 and 194 CE,61 dates Dosa’s son’s residency in Pola back to that period or immediately afterwards. The city of Neapolis was founded in Judaea near the Samaritan religious centre of Sichem by Vespasian in 72 CE, and was populated probably, at least at first, by Samaritans.62 Ancient historians note a severe punishment that befell the city for supporting a defeated contender to the imperial throne. The citizens of Neapolis were deprived of all civic rights by the imperial decree of Septimius Severus in 194 CE, for their long-standing armed support for his rival, Pescennius Niger; many were ruthlessly executed.63 This event might have instigated an en-masse exodus from Neapolis. Dosa’s son probably arrived in Pola in 194 CE, immediately after the defeat of Niger and while Syria was not yet divided into two provinces, Syria Coele and Syria Phoenice. Even if he had died later, in the third century, he could have kept in the funerary inscription the name of the province in which he was born and raised, not the one created after his departure and which was current at the time of his death. Septimius Severus revoked the punishment imposed upon the people of Palestine in 203-204 CE,64 but his brutal treatment of the people of Neapolis left a long-lasting mark on the survivors and forced them to leave their homes, never to return.

Map 3: Origins of private migrants to Istria from the East. Base map by Flappiefh, Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY SA 4.0); graphics drawn by the author.

A certain individual, whose name is not preserved (n. 23), was born in Ephesus and died in Pola probably in the first century CE, possibly in the period of Augustus. The fragmentary condition of the inscription does not allow us to decipher the abbreviation S.V.T.P. conclusively. It could mean s(oluto) v(oto) t(itulum) p(osuit), as proposed in the Inscriptiones Italiae X/1, but it could be also read as a funerary formula s(ibi) v(ivus) t(itulum) p(osuit). The shape of the partially preserved monument fits a tombstone better than a votive altar. It is worth mentioning that Ephesus was the recruiting base of the fleet of Mark Antony, whose many sailors, after the defeat at Actium, switched their allegiance to Augustus.65

C. Lorentius Tesifon (n. 42) bears a cognomen derived from Ctesiphon on the Tigris (Map 3). He arrived at Aegida, mod. Koper, in northwestern Histria, where he died and was buried in the third century CE.66 The status of Ctesiphon changed many times during the second and third centuries CE, from the western Parthian capital to a city in the Roman province of Mesopotamia, and vice versa. Ctesiphon was captured and unmercifully sacked by Roman armies several times during the second century CE, in the years of Trajan, Verus, and Septimius Severus.67 During the reign of Severus Alexander in the early third century, Ctesiphon became the capital of the newly established Sasanian empire.68 After several unsuccessful expeditions, the Romans recaptured Ctesiphon in 283 CE and kept it until the second half of the fourth century.69 Lorentius Tesifon probably arrived in Histria during the period when Mesopotamia was under Roman rule. His sarcophagus displays his good fortune, which indicates that he probably arrived in Italy as a free man.

Military Personnel

Determining the origins of veterans can be a daunting challenge. Some were undoubtedly natives of Histrian origin who returned to their homeland after completing their military service; the Moranus family from the vicinity of Motovun is a fine example of an autochthonous Histrian family whose members returned home after military service.70 Others were descendants of Italian colonists or their freedmen, permanently settled in Histria.71 Several veterans born elsewhere settled permanently in Histria. Some remained near the last place of military service, and others moved elsewhere to places of their choice, sometimes perhaps in the birthplaces of their wives. During the rule of the Julio-Claudian emperors, Italy was the most important source of recruits, but from the rule of Nero onwards, the number of Italians in the legions declined sharply.72 The descendants of Italians who settled in provincial colonies gradually replaced Italians in the legions after the middle of the first century CE.73 In fact, the most significant number of soldiers and veterans resettled in Histria originated in Italy. A few were stationed in Rome during active service.

Three Praetorians from the second, fourth, and ninth Cohorts buried in Histria belonged to the elite unit of the emperor’s bodyguards.74 Praetorian of the second Cohort L. Gallius Silvester (n. 44), probably of Gaul origins from northern Italy,75 was buried in Roč in the last quarter of the first century CE.76 Praetorian C. Furius C. f. Gemellus (n. 27) served in the fourth Praetorian Cohort. None of the cities of Regio X belonged to Furius Gemellus’ tribe, Arnensis. Since the Aemilian town of Brixellum, the Etrurian towns of Blera, Clusium, and Forum Clodi, the Umbrian town of Ocriculum, to Marrucini and Frentani in Regio IV belonged to this tribe, Furius Gemellus could have been born in central Italy, or, less likely, in a city outside Italy.77 His architectural stele with pilasters and gable dates to the first half of the first century CE.78 He may have come to Nesactium as a member of the entourage of the imperial family, which owned numerous estates in Histria since the era of Augustus.79 A veteran of the ninth Praetorian Cohort, C. Caulinius Sex. f. Maximus (n. 14) was the son of a newcomer from Syria who lived in the first half of the first century CE.80 Since it was not customary to admit newcomers from the remote Eastern provinces among the Praetorians, it may be presumed that his father came to Pola from Syria as a slave or as a free man before the beginning of his son’s Praetorian service. It is assumed that Caulinius Syrus was a freedman involved in trade.81 His son, Caulinius Maximus, certainly was domiciled in Pola, but it is uncertain whether he acquired this status by birth or upon registration in the census after relocation. His wife was a liberta of the powerful Palpellii family who, in Pola, rose through the ranks of the municipal aristocracy to the senatorial class.82

The military diploma of L. Vespennius L. f. Proculus (n. 31), miles of the Cohors X Urbana, found in Ježi near Umag, is dated to 194 CE. His tribus was Pollia and his city of origin was Faventia in Aemilia.83 The reason for his choice of settlement in northwestern Histria probably relates to the area’s flourishing economy.84 Like the praetorians, soldiers of the urban cohorts that maintained order in the city of Rome were recruited primarily among Roman citizens in Italy.85

Other soldiers with an attested presence in Histria served in military units stationed outside Italy. L. Campanius L. f. Pol(lia) Verecundus (n. 25) veteran of the fourth Scythian Legion and standard bearer, came to the Rovinj hinterland in the first century CE.86 As he was a centurion of the Cispadan Cohort, he came from a settlement on the south side of the Po river in Regio Aemilia. The Aemilian cities of Claterna, Faventia, Forum Corneli, Parma, Mutina, and Regium Lepidum, belonged to the tribus Pollia;87 any of them could have been his hometown. Similarly, C. Velitius M. f. (n. 38), a soldier of the Legio XX, was a native of Bononia in Aemilia assigned to Lemonia tribe.88 C. Titius C. f. Volt(ilia) (n. 29), a veteran of the Legio XV Apollinaris, died in Pomjan near Koper in the late first century BCE or early first century CE.89 The city of his origin was Vienna in Gallia Narbonensis (Map 2). From Augustus to Caligula, most of the provincials in the army came from Gallia Narbonensis (about 23%).90 The stele of [Te]dius Valens (n. 28), found in Karojba on the northeastern edge of the ager of Parentium, dates to the last quarter of the first century CE.91 Tedius Valens was born in Tergeste in Roman Histria and assigned to the Pupinia tribe, served as signifer of the Legion IIII Flavia Felix and received military marks of honour.92

Soldier Domitius Gracilis Ditio (n. 34)93 came to Tergeste from the inland of the province of Dalmatia, from the area between the source of the Krka and Zrmanja rivers to the Unac river area and between the rivers Una and Vrbas in modern-day western Bosnia and Herzegovina (Map 2).94 Inscriptions of the Ditiones are concentrated in the area of Vrtoče and Krnjeuša, not far from Bosanski Petrovac. Strabo lists Ditiones (Διτίωνες) among the Pannonian tribes in Illyricum that rebelled against Roman rule during Bato’s uprising.95 Pliny states that Salona, the capital of the province of Dalmatia, was the centre of jurisdiction for 239 decuriae of Ditiones.96 Such a large number indicates that decuria was a group of 10 family communities, comprising an average of 25 members. The average number of members of a decuria is estimated at about 250 people, so the tribe of the Ditiones may have included as many as about 60,000 people living in an area of approximately 5,000 square kilometres.97 Little is known about the Ditiones; they are thinly represented in the archaeological record and some autochthonous names (Bato, Dasas, Ditus, Tata, [V]elosu[nus]) have been preserved.98 For the most part, the Ditiones remained of peregrine status until the constitutio Antoniniana, hence military service was a way to gain Roman citizenship. Except for C. Titius from the provincial colony of Vienna and Domitius Gracilis from the province of Dalmatia, all other soldiers and veterans attested in the inscriptions from Histria were from northern Italy.

The inscription of Iulius Felix, assigned to the Arnensis tribe, soldier of the same Legion IIII Flavia Felix, is included in the corpus of the inscriptions of Tergeste. However, its original location was the Burnum military camp in Dalmatia, from where it was moved to Trieste in the early nineteenth century. Hence, it does not constitute testimony of a migrant to Histria and is not considered as such in this study.99

Were Migrants among the City Patrons?

City patrons were most often chosen among prominent local citizens, less frequently among the citizens of nearby towns in the region, and only exceptionally among high-ranking foreigners.100 City patrons coming from another city and those assigned to foreign tribes are listed apart as they stand out by their social status and by the nature of their connection with the municipality (Table 4).

Table 4: Inscriptions of Patrons from Different Cities or Assigned to a Foreign Tribe

| No | Publication | Inscribed Names | Origin | Type of Monument | Material | Site | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 48 | AÉ 2005 542 = EDCS-35500651 | T. Prifernius Paetus C. f. Settidianus Firmus, patron of Nesactium | Pola or Nesactium, Italy Regio X | Statue base | Limestone | Nesactium | 110-130 CE |

| 49 | IIt X/2 8 = EDCS-04200418 | C. Praecellius C. f. Pap(iria) Augurinus Vettius Festus Crispinianus Vibius Verus Cassianus, patron of Aquileia, Parentium, Opitergium and Hemona | Italy Regio X | Statue base | Limestone | Parentium | 175-200 CE |

| 50 | IIt X/4 30 = EDCS-04200620 | [C.] Calpe[tanus] Ran[tius] Quirinal[is Va]lerius P. f. Pomp(tina) F[estus], patron of Tergeste | Arretium, Italy Regio VII | Statue base | Limestone | Tergeste | 80-85 CE |

| 51 | AÉ 1888 132 = EDCS-10701347 | M. Carminius M. f. Pap(iria) Pudens, patron of Tergeste | Bellunum, Italy Regio X | Statue base | Limestone | Bellunum | 200-300 CE |

| 52 | AÉ 1976 252a = EDCS-10701348 | M. Carminius M. f. Pap(iria) Pudens, patron of Tergeste | Bellunum, Italy Regio X | Statue base | Limestone | Bellunum | 200-300 CE |

A patron from another city cannot automatically be considered a migrant, as he had no obligation to attend in person or even make a short visit to the municipality that declared him their protector, let alone settle permanently. City patrons of senatorial or equestrian rank, regardless of their actual residence, were included by cooptation among citizens of the municipality in question and were under no obligation to establish a presence.101 If the patron visited personally, it was only for a short time, unless he had property or other private interests therein. Accordingly, many patrons from other cities should be regarded as temporary or seasonal migrants, not permanent settlers.

The situation may be different for patrons who changed their domicile by adoption or for those from families who have resettled but retained their original tribe.102 In this sense, the example of T. Prifernius Paetus C. f. Settidianus Firmus, consul and patron of Nesactium in the second century (n. 48), is indicative. He probably served as consul suffectus in the period between 106 and 108 CE and provincial legatus of Moesia Superior in 112.103 He was born C. Settidius C. f. Firmus and adopted by T. Prifernius Paetus, consul in 96 CE and homo novus from an equestrian family, who adopted at least two more sons.104 One of these adoptive sons was born in the powerful Histrian senatorial family of Laecanii Bassi, which convincingly links the Prifernii with southern Histria. Prifernius Paetus Settidianus Firmus probably was a son (or grandson) of the quaestor urbanus C. Settidius Firmus (n. 19) and an older brother of the consul suffectus in 112 T. Settidius Firmus (n. 20), both known from inscriptions from Pola. The senatorial family of the Settidii owned estates near the Nesactium.105 The family of his adoptive father, Prifernius Paetus, originated in central Italy. The epigraphic testimonies show the presence and possessions of his adoptive father in the territory of Trebula Mutuesca, in Samnium.106 Construction material signed T. Priferni Paeti from Castrimoenium in Latium marks the possessions of Prifernii Paeti.107 T. Prifernius Paetus Settidianus Firmus (n. 48) is an example of a citizen who migrated from Histria to central Italy. The Nesactium inscription does not provide his tribe, but it is reasonable to assume that it was either the Pupinia tribe (of his biological father) or the Quirina tribe (his adoptive father’s, from Trebula Mutuesca).108 The change of tribe was possible in the case of adoption, but not mandatory. In the Republican period, initially, the rule was that an adoptive son should take the tribe of his adoptive father, but the adoptive sons could be left in their old tribes, which allowed them the possibility of belonging to two tribes. An adopted son could keep the tribe of his origin and pass it on to his descendants. The possibility to choose between tribes came to the fore in the period of adoptive emperors.109 T. Prifernius Paetus Settidianus Firmus set aside in his will the sum of 100,000 sesterces for the erection of his statue with a pedestal on the occasion of the award of patronage by the municipium of Nesactium, which was confirmed and approved by the ordo decurionum. Before the statue was placed, one-twentieth of the state inheritance tax, i.e. 5,000 sesterces, was deducted from the sum.

C. Praecellius C. f. Pap(iria) Augurinus Vettius Festus Crispinianus Vibius Verus Cassianus (n. 49) was very young (clarissimus iuvenis) when he was honoured with a statue in Parentium and had already been the patron of Aquileia, Parentium, Opitergium, and Hemona (Emona). As the patron of four cities, he had to be received formally by the citizens of each one of them. His origin is not entirely clear. The Praecellii were widespread in Bellunum, and the Papiria tribe belongs to Bellunum and Opitergium as well. It is generally considered he was adopted by a family from Bellunum, yet some uncertainty remains as to whether he retained the hometown tribus or changed it after adoption, as the Vettii were attested in Bellunum, Opitergium, and Aquileia.110

Calpetanus Rantius Quirinalis Valerius Pomp(tina) Festus, consul in 71 CE and patron of Tergeste (n. 50), is the last known member of the senatorial family of Calpetani.111 He was born in the Arretine family of the Valerii Festi assigned to the Pomptina tribe and adopted by senator C. Calpetanus C. f. Rantius Sedatus Petronius.112 The Pomptina tribe was the official tribe of Arretium.113 The list of patrons of Tergeste was updated with the name of eques M. Carminius M. f. Pap(iria) Pudens (nos. 51-52), who was, among other offices, patron of the plebs urbana, i.e. the poorest class of the population of Rome, patron of the Catubrini, and curator of Mantua and Vicetia. Two bases of his statues were found in Bellunum.114 Bellunum gave two known patrons of Histrian cities, Praecellius Augurinus (n. 49) and Carminius Pudens (nos. 51-52), both assigned to the Papiria tribe belonging to Bellunum.115 P. Septimius P. f. [---], eques Romanus and patron of Tergeste, may conditionally join the list, as it is not possible to determine whether he was a native of Tergeste or another city.116 Not counting Septimius, whose origo remains unknown, and Carminius Pudens (of equestrian rank), all other patrons of Histrian cities elected among the citizens of other cities were of senatorial rank with successful careers who entered senatorial families by adoption. They adopted a polyonymous nomenclature comprising both old and new names.117

The process of determining if some patrons can be considered migrants returns an interesting result. Prifernius Paetus Settidianus Firmus (n. 48) was a native citizen of Pola or neighbouring municipium Nesactium, from a family that maintained its affiliation to the tribe of Tergeste for generations despite its relocation. A successful career took him from southern Histria to distant parts of the Roman Empire, but he maintained a connection with his homeland, to which he bequeathed a donation for the erection of his statue on the Nesactium forum. Despite his tribe being foreign to Pola and Nesactium, he actually migrated from Histria rather than to it. Among citizens who temporarily left Histria to build a career, some were assigned to a tribe foreign to their hometown: T. Settidius C. f. Pupin(ia) Firmus (n. 20), and possibly his ancestor C. Settidius C. f. Pup(inia) Firmus (n. 19), P. Palpellius P. f. Maec(ia) Clodius Quirinalis (n. 37), and T. Prifernius Paetus Settidianus Firmus (n. 48).

Praecellius Augurinus Vettius Festus (n. 49) was proclaimed patron of Parentium and three other cities in northeastern Italy at a young age, and there is no indication that he established any connection with Parentium or ever visited it. Calpetanus Rantius Quirinalis Valerius Festus (n. 50) retained the tribe of his hometown after his adoption. Both he and his adoptive father were from central Italy. It is assumed that his land holdings or other economic interests in Tergeste were the reason for his appointment as patron of the colony.118 That would imply at least occasional visits to Tergeste. No other evidence of his connection with Tergeste is preserved, as is the case with Carminius Pudens from Belluno (nos. 51-52). Senatorial and equestrian patrons from other cities declared patrons in Histrian cities came from central and northeastern Italy. If economic interest connected them with Histria, they could be categorised as temporary or seasonal migrants.

Unlike patrons, curators of municipalities (curatores rei publicae) were obliged to live in the municipality whose finances were entrusted to them. This renders them temporary migrants. Curatores were regularly selected from another, not too remote, municipality. Decius Mettius Sabinianus (n. 26), curator of Pola, was a native of Concordia, where the grateful colony of Pola erected a monument in his honour.119 Still, Papirius Secundinus from Pola was appointed curator of Flanona, a municipium in the Istrian part of the province of Dalmatia but endowed with Italian rights (ius Italicum), which obliged him to leave Pola occasionally.120

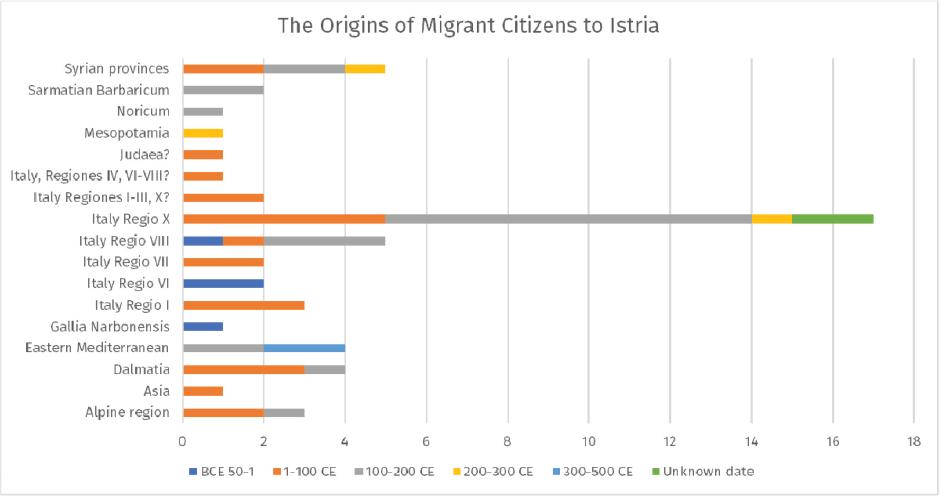

Overall, the list of migrants among Roman citizens in Histria reveals some general flows of migration and their course over the centuries (Table 5). By far, the largest number of migrants to Histria came from neighbouring northeastern Italy (Regio X) in the first three centuries CE (Map 2). Looking only at Italy, they are followed by two equally large categories. One came from the undefined, somewhat more remote regions of northern Italy and the region south of the Po river (Regio VIII), between 15 BCE and 300 CE. Another category, chronologically the earliest, came from the Central Italian regions and Campania (Regio I, VI, VII) in the period between 50 BCE and 100 CE. The influence of powerful senators on migration is noticeable. All three attested newcomers from Neapolis in Campania (nos. 17, 33, and 37) were related to the Histrian senatorial family of Palpellii, who prospered in the first half and the middle of the first century CE. Inscriptions of soldiers and veterans settled in Histria date mostly to the period between 15 BCE and 100 CE, except a military diploma dated to the end of the second century CE (n. 31). All soldiers and veterans were Italians, except one from the province of Gallia Narbonensis (n. 29) and another from the inland of the province of Dalmatia (n. 34). Most were born in the region of Aemilia. One praetorian was the son of a Syrian, domiciled in Pola (n. 14). After Italy, Eastern Mediterranean provinces were the main source of settlers throughout the entire Imperial period (Map 3). Inscriptions confirm that Histria attracted newcomers endowed with civil rights, merchants from Asia Minor and more remote Middle East regions (the latter more prominently). Migrants from the Western provinces were very rare, except Dalmatia, which shows the strongest connection with Histria.

Table 5: The Origins of Migrant Citizens to Histria

|

The Deposed Roxolanian King Rasparaganus: Amicus Populi Romani or Relegatus?

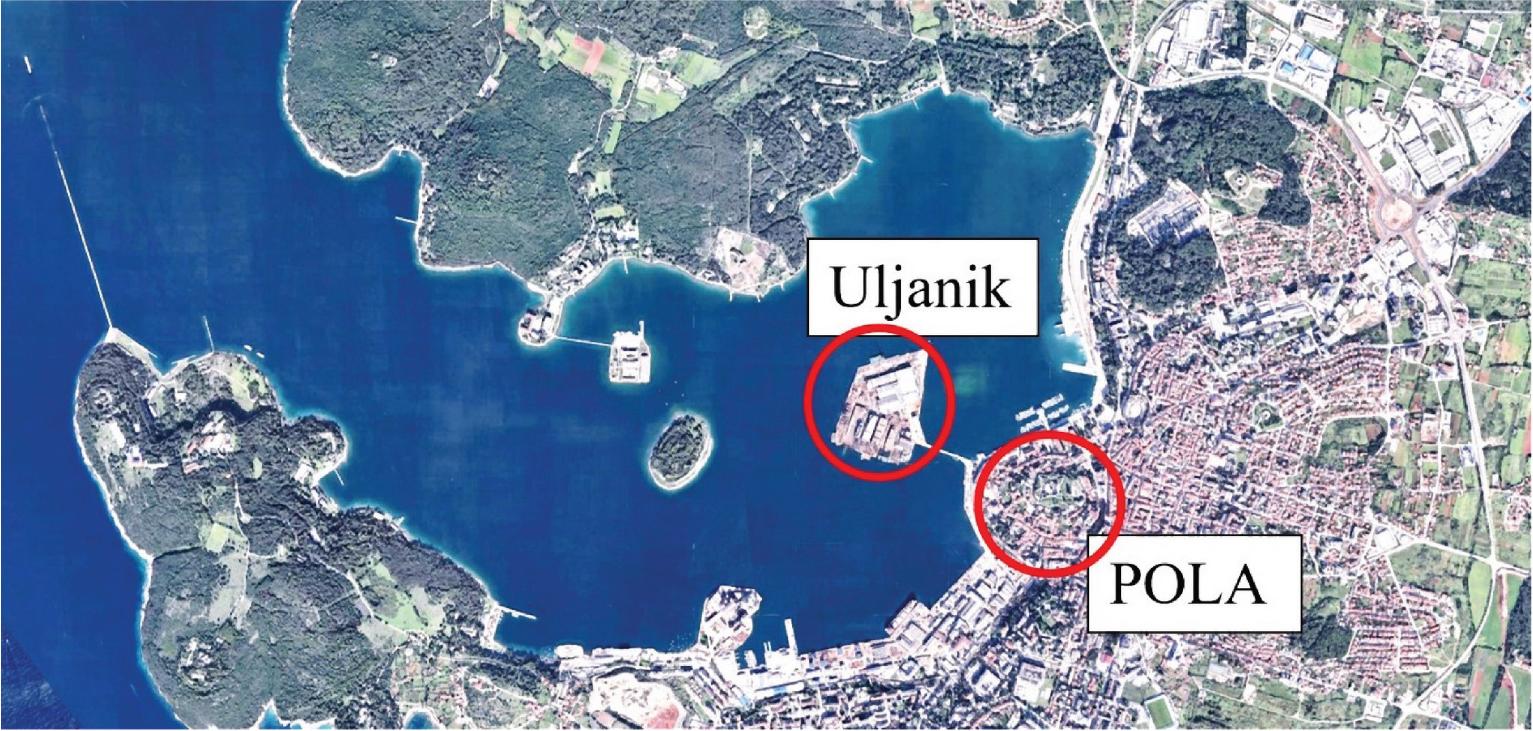

The case of Rasparaganus has instigated considerable debate. King of the Sarmatian tribe of the Roxolani, Rasparaganus, died and was buried with his family on the small island of Uljanik in Pola harbour, on which the shipyard is located today (Map 4).121 Two funerary inscriptions, both mentioning Rasparaganus, were found on Uljanik. The inscription of P. Aelius Rasparaganus, king of the Roxolani (n. 7), was set by his unnamed wife: Aelio Rasparag[a]no / regi Roxo[la]noru[m] / [u(xor)] v(iva) [f(ecit)].122 The second inscription marked the burial place of P. Aelius Peregrinus (n. 8), son of the Sarmatian king Rasparaganus, his wife Attia Q. f. Procilla, and all family freedmen: P(ublius) Aelius Peregrinus reg[is] / Sarmatarum Rasparagani / f(ilius) v(ivus) f(ecit) sibi et Attiae Q(uinti) f(iliae) Procillae lib(ertis) l[iber]/tabusq(ue) posterisq(ue) eorum.123

Map 4: Aerial photograph of Pola and its harbour. Source: Google Maps; graphics drawn by the author.

Both inscriptions traditionally were interpreted as sarcophagi fragments.124 This is not entirely certain due to their fragmentary condition. The lack of figural decoration on both sides of the inscription field on both monuments does not correspond to the sarcophagi typology known from Istria and northern Italy. Neither of the inscriptions was placed initially on the sarcophagus lid. While the monument of Rasparaganus shows the profiled lath above the framed inscription field, which allows us to assume it was part of a sarcophagus, the inscription of his son, P. Aelius Peregrinus, within an unframed inscription field bears no lath on the upper edge or recesses for receiving the lid. It is more likely that the inscription of Aelius Peregrinus and his family was built into a mausoleum, a large square masonry monument, possibly in the form of a temple and possibly with sculpture.

The Scriptores Historiae Augustae record minimal historical notes on the king of the Roxolani. The book on Hadrian briefly outlines historical events with which the persons buried on the island in the port of Pola can be associated, but not the king’s name: Audito dein tumultu Sarmatarum et Roxolanorum praemissis exercitibus Moesiam petiit... Cum rege Roxolanorum, qui de inminutis stipendiis querebatur, cognito negotio pacem composuit.125 We read that the Roxolanian king was displeased and complained because of the diminution of the subsidy (stipendium) paid by the Romans. Hadrian investigated his case and made peace with him. Army deployment and imperial investigation recorded in this passage is literally all the textual evidence we have about this episode. Hadrian’s conflict with the Roxolani dates to the end of 117 or to the spring of 118 CE. The reasons and manner of Rasparaganus’ arrival in Pola have been interpreted differently, yet two main interpretations of historical and archaeological sources stand out: either Rasparaganus was imprisoned for life by Hadrian on the island, or he voluntarily relocated with his family to a small island in the port of Pola.126 The first ambiguity concerns the stipendium and to whom it was actually paid. The generally accepted interpretation is that Rome has been paying a subsidy to the Roxolani since the era of Trajan, thus buying peace and their neutrality.127 Hence, some scholars argue, historical sources do not support or dismiss in any way that a conciliation took place between Hadrian and Rasparaganus, wherein the king was made a Roman citizen and Hadrian elevated him to the status of a friend of the Roman people (amicus populi Romani). Rasparaganus and his son were afterwards exiled from their homeland by a rival anti-Roman group among the Roxolani and the Iazyges, possibly early in the reign of Antonius Pius.128 This interpretation does not consider the reasons why a king of the Roxolani, with his whole family and a potential heir, remained isolated for life on the rocky islet in the port of Pola, especially if he owned land elsewhere in the Pola area, nor how he was isolated for life without land holdings that could provide for a dignified life.

According to a more straightforward interpretation, Hadrian removed the Roxolanian king, placed him in lifelong exile on the island, and installed a new puppet ruler in his place.129 Certainly, being far from his homeland (Map 3), Rasparaganus could not force the Roman emperor to pay his people compensation as a guarantee of peace and non-aggression. There is also a possibility that this episode should be understood differently, literally as it is written: the king of the Roxolani complained of a reduction in the amount of support for him personally and his family, not the amount paid to his people. Strong Roman criminal law arguments and archaeological ones support the theory that the Roxolanian king with his entire family was sentenced to life in solitary confinement on the islet of Uljanik by Hadrian.130 The king and his son were granted Roman citizenship and all the conditions for a comfortable life as a result of Hadrian’s reconsideration of the case. The sheer size of the funerary monuments on the islet testifies to the reputation and wealth of Rasparaganus’ family members. Apparently, Hadrian made peace with Rasparaganus by forcing him and his son into lifelong exile, in the form of captivity reserved for the highest social layers, relegatio ad insulam,131 and paying him a generous sum to secure a dignified life. The payment had a purpose since the deposed Roxolanian king had no civil rights, possessions, or freedom of movement outside the islet. In any case, the granting of Roman citizenship was a prerequisite for relegatio ad insulam.

Another episode from Hadrian’s life can be associated with the rebellion of the Roxolani and peace with Rasparaganus. In 121-123 CE, Hadrian built a tomb for his favourite horse, Borysthenes, in Gallia Narbonensis. The funerary inscription from Apt, Vaucluse, terms the fast horse Borysthenes as Alanus, Caesareus veredus, and clarifies that it died young and unharmed.132 Borysthenes, named after the ancient name of the river Dnieper (Map 3),133 was bred in the land of nomadic Alans north of the Black Sea. Sarmatian Roxolani were one of the Early Alanic tribes, contemporary and closely associated with the first Alans, who in the time of Hadrian lived east of the Danube delta.134 Medieval sources remember the Roxolani as a prominent tribe from which the kings of Alans were chosen.135 Their Indoeuropean name was explained as *Rhox- or *Ruxs- Alans, meaning luminous or shining Alans.136 Hadrian probably obtained Borysthenes in early 118 CE following the rebellion of the Roxolani, possibly as a ruler’s gift of reconciliation. In 121-123 CE Borysthenes would be at his best, young and strong, just as described in the epitaph. It remains uncertain whether Borysthenes was a gift from Rasparaganus.

The Legal Status of Migrants: Were Migrants Allowed Entry to the Public Baths?

Free persons who resettled and changed their domicile were termed incolae.137 The term includes members of municipalities with Roman or Latin rights, or indigenous communities without them. The issues of the legal status of settlers were generally regulated by city law or imperial edict. The legal status of incolae and the framework of the term developed in the last centuries of the Republic and in the Early Imperial period in parallel with other legal categories of the organisation of territorial communities, such as attribution and contribution.138 Certain problematic aspects were resolved by special decisions at the local level, as evidenced by the inscription found near Buje in northern Istria, which records the decurions’ permission to the colonists, settlers (incolae), and foreigners (peregrini) to bathe in the thermae free of charge (Map 1).139 Free entrance is one of the most frequently attested types of benefaction in connection with public baths.140 Relevant inscriptions regularly list various legal categories of users, even slaves. The choice of categories depended on the local situation and needs, and the inscription from Buje is the only one that contains the combination colonis, incolis, peregrinis in the context of bathing. An epigraphic quasi-formula containing citizens, incolae, and peregrines is attested in only a few different administrative decisions and cannot be regarded as a formula per se.141

The very fact that the inscription was put in place indicates that the decision was preceded by a debate and different views on who has the right to use the thermae. The process and public announcement of the decision in a visible location, probably along Via Flavia that connected the Histrian colonies, was intended to resolve any doubts over the right to free use of the public baths.

The decurions mentioned in the inscription could only refer to the colony of Tergeste. The baths can be identified with Quaeri, marked on the Tabula Peutingeriana with the symbol for thermal baths.142 The nearest thermal baths are Istarske Toplice, 25 kilometres away from Buje (Map 1).143 There are no thermal springs close to the river Rižana (Formio in antiquity), about 40 kilometres from Buje, so Istarske Toplice remains the most likely option. If Quaeri can be identified with Istarske Toplice, it can be assumed that the autochthonous Histrian communities used the thermal spring free of charge by customary law, and after the extension of the jurisdiction of the colony of Tergeste to northern Histria, this right was simply extended to all inhabitants of the colony, but also to newcomers and travellers. The colonists who came to the thermae in northern Histria can be described as temporary migrants, as they arrived from the urban centre to a remote place assigned to the territory of the colony of Tergeste in the Augustan period by some kind of legal procedure (attribution, contribution, or full inclusion).144 Incolae, on the other hand, represented a heterogeneous group including permanently or at least seasonal migrants, as well as permanently settled members of native Histrian communities. Incolae of Roman citizenship were new domiciled citizens or citizens without legal domicile in the territory under the administration of the colony of Tergeste, who engaged in economic activities yet were nevertheless obliged to fulfill duties to the colony.145 Citizens changed their domicile by simply registering in the census in their new municipality.146 In order to prevent evasion of registration in the new place of residence and avoidance of ensuing obligations, the retention of a double domicile was permitted. At the latest since the rule of Hadrian, incolae were required to meet requested obligations both in their host community and their place of origin.147 The exceptions were veterans who enjoyed the privilege of immunity, even if they accepted to pursue a municipal career.148 Valerius Priscus, a clothing merchant from Aquileia who came to northern Histria seasonally for the purchase of wool, was one of those incolae – Roman citizens.

In the extraordinary case of the inscription from Buje, the incolae were not only newly settled Roman citizens but also members of the indigenous peregrine or Latin communities in the interior of northern Histria and in the south eastern Alps.149 The native inhabitants of peregrine status whose territories fell under the jurisdiction of the colony were also termed incolae.150 Autochthonous peregrines in Histria were certainly not immigrants, but as they changed domicile by administrative change without leaving their homes, they entered the category of incolae. Therefore, the term incolae on the inscription from Buje referred to migrant Roman citizens as well as members of the indigenous peregrine communities of northern Histria. The third category included in the quasi-formula, peregrines, were foreigners, free people without Roman citizenship but on friendly terms with the Roman state. Since the term incolae on the inscription from Buje embraces the entire permanently settled, indigenous Histrian population regardless of citizenship, peregrines were foreign passers-by, i.e. temporary immigrants.151 The distinction between citizens and peregrines disappeared after the constitutio Antoniniana in 212 CE. In some cases, individuals of foreign descent bear the personal name (cognomen) Peregrinus, which is indicative of immigrant status. The funerary altar of Trosius Peregrinus (n. 46), son of Trosius Severus, dates to the first century CE and shows that the family moved to Tergeste.152 The case of the Trosii is comparable to Aelius Peregrinus, son of the king of the Sarmatian Roxolani Aelius Rasparaganus, discussed above.

Conclusion

Private migration to Histria occurred for different reasons: to seek economic prosperity and a better life; to escort a family member; to trade or engage in business of an occasional or seasonal nature; to visit religious sites and thermae; or to settle permanently. The official reasons for migration were equally varied: to perform administrative and religious municipal duties; to escort a military commander, senator or member of the Imperial family; even forced relocation by the emperor’s decision. The number of migrants who came to Histria of their own free will is relatively small and concentrated in the colonies of Pola and Tergeste. They are recognisable by the language of the inscription (especially if written in Greek) and their origin or topophoric names inscribed on stone. The municipal functions in a foreign city are indicators of a possible newly settled citizen. Being enlisted in a foreign tribe is a reliable indicator of foreign origin only in the case of soldiers and veterans. In the case of high-ranking commanders and magistrates, it could have been the result of adoption or resettlement that took place several generations ago.

Settlers brought with them their customs and beliefs, sometimes a local tradition, which are embedded in the design of funerary monuments, recognisable in the style of Catusius’ sarcophagus from Pola, for instance (n. 13). Inscriptions confirm various types of migration in Histria, seasonal, temporary, and permanent. Valerius Priscus (n. 32), a trader of woollen garments from Aquileia, visited seasonally to procure wool at the foot of the Učka mountain in northern Histria, where he died. Temporary visitors were clearly registered in important religious and spas away from urban, such as the spa and the sacred source of the river Timavo between Tergeste and Aquileia, or the spa at Quaeri. People from the neighbouring regions of Venetia and Noricum visited sacred healing springs to find cured and comfort from illness.

Most migrants settled permanently in Histria. Members of the municipal aristocracy retained their status after relocation, moving from one city council to another, much like the Augustals. For patrons from another city, there is no evidence that they had ever visited the Histrian town that elected them as patrons, and their categorisation as occasional or seasonal migrants remains questionable. The curators, however, were obliged to visit occasionally the city whose finances they supervised; for example, Decius Mettius Sabinianus from Concordia (n. 26) can be considered a temporary migrant in Pola. Most migrants came from neighbouring regions in northern Italy, indicating that the main direction of migration was from the centre to the extremities of Italy, from west to east. The presence of the Imperial family through Histrian estates run by imperial slaves and freedmen starting with Augustus, and senatorial families in Histria, proved to be a decisive factor in attracting migrants from Italy. Second in number were migrant citizens from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, probably merchants.

The paper focused in a single Roman region, perhaps inevitably. A study of a larger area (the entire Regio X for example) would require much more space, whereas narrowing down the scope to a smaller area could only mean discussing a municipality. The latter is too small and locally oriented, to the effect that it would have deterred wider applications of the findings, and their contextualisation into wider debates over migration. Despite its potential uses for researchers interested in migration, a wider discussion of migration patterns in the Roman Empire, or other aspects of migration in Histria, are subjects for other studies, which the paper aspires to inform.