Introduction

In studies of ancient seaborne trade, the model of widespread tramping outlined in Horden and Purcell’s The Corrupting Sea (2000), derived from studies of Medieval Mediterranean trading patterns and retrojected into antiquity, has proven popular among historians of ancient economy and society.1 This model likens the majority of seaborne merchants to roving peddlers, tramping from one place to the next trying to sell their wares; Horden and Purcell characterise this activity as ‘Brownian motion’ and ‘background noise’, even extending it beyond local horizons to long-distance trade.2 However, Alain Bresson and Pascal Arnaud have argued that maritime trade was less random than the ‘Brownian motion’ model suggests, and they propose a firmer distinction between how interstate and intra-state maritime trade functioned in the Classical Greek world. This approach holds that seaborne traders operating between different states were required to sail to and from emporia – that is, ports legally designated for this purpose by the state in question and monitored by magistrates of several sorts.3 There is little room in this model for building up and subsequently selling a cargo piecemeal by tramping speculatively along the coastline from port to port. However, the model does admit that interstate journeys could be segmented, a mixture of short hops between escales techniques (that is, navigational landings) and longer open-sea passages.4 Nevertheless, this model does not reduce all maritime trade to inter-state emporion-trade, for it freely admits the existence of much low-level, intra-state relay trade conducted via minor ports and moorages, of a sort that can resemble the cabotage model of Horden and Purcell in the sense of short-range coasting, though the degree to which this equates to tramping is up for debate.5 Such low-level intra-state trade and the minor regional moorages and harbours that served it were the preserve of the legal residents of the region in question: the state excluded foreign merchants from this activity, whose business lay solely with the emporion. Of course, adverse weather might force foreign sailors to seek shelter in a minor regional moorage, but the conduct of trade there was not permitted.6 Yet, the model of Bresson and Arnaud accepts that not everyone followed the rules and that some degree of smuggling should be acknowledged.7

The present article investigates the practical problems posed by the co-existence of these two tiers of trading activity and their oversight by ancient Greek states by exploring a case study where the division between these tiers becomes blurred. The events in question are described in the speech Against Lacritus, attributed (rightly or wrongly) to the orator Demosthenes ([Dem.] 35, c. 350 BCΕ).8 The speaker9 relates how he and his partner loaned 3,000 dr to two Phaselites – Artemon and Apollodoros – to finance a trading voyage from Piraeus to the Black Sea in a ship skippered by a man named Hyblesios; the terms were written up in a contract that Artemon’s elder brother Lakritos, a Phaselite residing at Athens, helped to broker. According to the speaker, the borrowers did not abide by the terms of the contract and, among other underhand deeds, behaved as follows on their return to Attica:

ὃ δὲ πάντων δεινότατον διεπράξατο Λάκριτος οὑτοσί, δεῖ ὑμᾶς ἀκοῦσαι· οὗτος γὰρ ἦν ὁ πάντα ταῦτα διοικῶν. ἐπειδὴ γὰρ ἀφίκοντο δεῦρο, εἰς μὲν τὸ ὑμέτερον ἐμπόριον οὐ καταπλέουσιν, εἰς φωρῶν δὲ λιμένα ὁρμίζονται, ὅς ἐστιν ἔξω τῶν σημείων τοῦ ὑμετέρου ἐμπορίου, καὶ ἔστιν ὅμοιον εἰς φωρῶν λιμένα ὁρμίσασθαι, ὥσπερ ἂν εἴ τις εἰς Αἴγιναν ἢ εἰς Μέγαρα ὁρμίσαιτο· ἔξεστι γὰρ ἀποπλεῖν ἐκ τοῦ λιμένος τούτου ὅποι ἄν τις βούληται καὶ ὁπηνίκ᾽ ἂν δοκῇ αὐτῷ. καὶ τὸ μὲν πλοῖον ὥρμει ἐνταῦθα πλείους ἢ πέντε καὶ εἴκοσιν ἡμέρας, οὗτοι δὲ περιεπάτουν ἐν τῷ δείγματι τῷ ἡμετέρῳ, καὶ ἡμεῖς προσιόντες διελεγόμεθα, καὶ ἐκελεύομεν τούτους ἐπιμελεῖσθαι ὅπως ἂν ὡς τάχιστα ἀπολάβωμεν τὰ χρήματα. οὗτοι δὲ ὡμολόγουν τε καὶ ἔλεγον ὅτι αὐτὰ ταῦτα περαίνοιεν. καὶ ἡμεῖς τούτοις προσῇμεν, καὶ ἅμα ἐπεσκοποῦμεν εἴ τι ἐξαιροῦνταί ποθεν ἐκ πλοίου ἢ πεντηκοστεύονται.

[Dem.] 35.28-29

You must now hear the most dreadful thing of all which this man Lakritos has done, since it was this man who oversaw the whole affair. For when they arrived here, they did not sail into your port, but moored in Thieves’ Harbour (Phōrōn Limēn), which is outside of the signs designating your port; and it is the same thing to moor in Thieves’ Harbour as it is if someone were to moor in Aigina or Megara, for anyone can sail out from that harbour to wherever he wishes and at any time he deems fit. And their ship was moored there for more than twenty-five days, whilst these men strolled about in our sample-market (deigma); and we approached and spoke with them, urging them to see to it that we should receive the money as quickly as possible. And they were in agreement and kept saying that they wished to bring about that very end. At the same time as we were with them, we were keeping an eye open to see if they were unloading anything from a ship anywhere or paying the two-per cent tax.

After stringing the speaker along with excuses, a startling fact eventually came to light. Lakritos admitted that Hyblesios’ ship had sunk off the Crimean coast – and since the contract was null and void in the event of a shipwreck, the borrowers did not have to repay the loan ([Dem.] 35.30-31; cf. 56.22). The ship on which the Phaselites had subsequently sailed, and which later moored at Thieves’ Harbour, was skippered by another Phaselite, whose name is not given ([Dem.] 35.52-55) – and none of these details was apparently disclosed to the speaker straight away.

The significance of this passage for the debate over the division between interstate and intrastate maritime trade has often been misconstrued by modern scholars due to the common belief that Thieves’ Harbour was a smuggler’s cove (or, according to one hypothesis, a pirate’s port) and that the speaker was, in a roundabout manner, implying that the Phaselites were smuggling goods. In this article, I argue that the imputation of smuggling is far from certain. Instead, it is more likely that the Phaselites were trying to make use of the facilities at Piraeus for their regular trading activity whilst delaying news of their return from reaching the ears of their creditors. Above all, they moored at Thieves’ Harbour – a moorage used for local coastal trade – in order to keep from one very important fact from their creditors for as long as possible: that the ship carrying the cash loan and cargo had sunk and that the Phaselites had returned to Attica on board a different vessel. Our exploration of this episode will require an in-depth look at the location of Thieves’ Harbour (§I), the practicalities of local coastal trade in Attica (§II), and certain weaknesses in the Athenian state’s oversight of maritime trade – weaknesses that cunning and unscrupulous merchants knew how to exploit (§III).10

I. Thieves’ Harbour: Its Location and Traditional Interpretations of its Function

The description of the behaviour of the Phaselites on their return to Attica, quoted above, suggests that Thieves’ Harbour lay within walking distance of Piraeus. Strabo provides a more explicit statement of its location, listing toponyms along the approach to Piraeus from the west:

ὑπὲρ δὲ τῆς ἀκτῆς ταύτης ὄρος ἐστὶν ὃ καλεῖται Κορυδαλλός, καὶ ὁ δῆμος οἱ Κορυδαλλεῖς· εἶθ᾽ ὁ Φώρων λιμὴν καὶ ἡ Ψυττάλεια, νησίον ἔρημον πετρῶδες ὅ τινες εἶπον λήμην τοῦ Πειραιῶς· πλησίον δὲ καὶ ἡ Ἀταλάντη ὁμώνυμος τῇ περὶ Εὔβοιαν καὶ Λοκρούς, καὶ ἄλλο νησίον ὅμοιον τῇ Ψυτταλείᾳ καὶ τοῦτο· εἶθ᾽ ὁ Πειραιεὺς καὶ αὐτὸς ἐν τοῖς δήμοις ταττόμενος καὶ ἡ Μουνυχία.

Strab. 9.1.14

Above this shore is a mountain which is called Korydallos, and also the deme Korydalleis; next one comes to the Thieves’ Harbour (Phōrōn Limēn), and to Psyttaleia, a deserted, rocky islet which some have called the eyesore of Piraeus. And also close by is Atalantē, homonymous with the island near Euboea and the Locrians, and this is another islet like Psyttaleia. Next is the Piraeus, which also is numbered among the demes, and Mounychia.11

Thieves’ Harbour was therefore located on the coast to the west of Piraeus, somewhere between modern Keratsini and Perama; it still existed when Dodwell visited the area in the early nineteenth century. Travelling from Eleusis to Piraeus, the same route as Strabo’s itinerary, he wrote:

As we approached the Piraeus, Port Phōrōn became visible, at the foot of Aigaleos. The port is at present known by the name of Κλεφθο-λιμανη, ‘The Thieves’ Port;’ and the same sense was designated by its ancient appellation. A neighbouring tower is called Κλεφθο-πυργος, the Thieves’ Tower, and here are some traces of antiquity; the remains, probably, of a small fort.12

The exact location now lies under the heavy industrial development of this stretch of coastline, but a good candidate for Dodwell’s Κλεφθο-πυργος (sic.) is marked on Curtius’ and Kaupert’s Karten von Attika as the ‘Venetianischer Thurm’ (‘Venetian Tower’, Karten von Attika Bl. III). Another nineteenth-century traveller, W. M. Leake, wrote that the eastern entrance to the strait of Salamis was demarcated by the western cape of Port Phōrōn on the mainland and the cape of Agia Varvara on Salamis (the easternmost extremity of the island, close to Psyttaleia).13 Leake placed Phōrōn Limēn at Keratsini, the bay to the east of this tower, and not at the bay of Trapezona (mod. Drapetsona), which he thought was too close to Piraeus.14 Curtius and Kaupert were inclined to agree with him.15

Map I: Karten von Attika Bl. III. (1) foothills of Mt. Aigaleo; (2) the ‘Venetianischer Thurm’; (3) Keratsini; (4) Trapezona; (5) Leipsokoutala, ancient Psyttaleia. Modern Perama lies beyond the boundaries of this map, extending to the left of (1) and (2).

Even though the approximate location of Thieves’ Harbour somewhere between modern Perama and Keratsini is clear, its function is rather less so. Many scholars, on the basis of nothing more than the passages from [Demosthenes] and Strabo quoted above – but above all the striking name Phōrōn Limēn – have concluded that a smuggler’s cove existed virtually round the corner from Piraeus where cargoes were surreptitiously unloaded away from the prying eyes of the pentēkostologoi – the officials tasked with exacting a 2% tax on imports and exports in Piraeus.16 Isager and Hansen, alternatively, translate Phōrōn Limēn as ‘Pirates’ Harbour’, and write: ‘Presumably, the pirates’ harbour originally served as a refuge for those pirates who carried their booty to Attica’.17 It is important to look more closely at this issue, for as we shall see, the association with smuggling (or piracy) is far from certain and does not make good sense of what is described in the Against Lacritus.

The least likely of the hypotheses canvassed above is that to do with piracy. Objections can be levelled on linguistic and historical grounds. Isager and Hansen translate phōr as pirate because the word is glossed as leistēs by the Suda and the Lexica Segueriana.18 The term leistēs, as de Souza has noted, can apply both to the terrestrial and maritime sphere, and therefore can mean either ‘bandit’ or ‘pirate’.19 Presumably, the maritime context and pairing of the word with limēn, ‘harbour’, led Isager and Hansen to choose ‘pirate’ from these two options. Much better than relying on late lexica, however, is a contextual analysis of the semantic range of the term phōr in contemporary Greek texts, which reveals that the word is far less specific: it is a general term for thief and a synonym of the much more common word kleptēs. For instance, Herodotos repeatedly uses phōr in his tale of Pharaoh Rhampsinitοs and the thief (Hdt. 2.121) to label the men who burgle the Pharaoh’s treasure chamber (he also uses the word kleptēs at 2.121β as a synonym; cf. 2.174). Plato uses the word in the same way in the Laws (874b-c; 954 b-c) in reference to housebreakers. All other contemporary attestations of the word lack maritime connotations and are just general references to theft and thieves.20 The translation ‘Thieves’ Harbour’, therefore, more accurately captures the semantics of the locution in Classical Greek – there are no linguistic grounds for translating Phōrōn Limēn narrowly as ‘Pirates’ Harbour’.

Isager and Hansen rightly note that Phōrōn Limēn cannot have been used by pirates by the fourth century and suggest that it got its name during the archaic period.21 However, one ought not to view piracy in archaic Attica as an illicit activity conducted by outcasts who required some secret bolthole but as an integral feature of archaic society practised openly that gradually faded over time. Small raiding crafts such as pentekonters and triakonters, belonging to local members of the elite and presumably used for plundering voyages, were still to be seen on the coast near Vouliagmeni later in the sixth century.22 In the fifth century, Athens’ maritime empire endured partly because it kept the seas clear of piracy and protected merchants, supporting economic growth among its subject cities.23 Privately owned warships became a thing of the past after the Persian Wars, and the idea of acquiring one could engender heated debate in the Assembly.24 In short, an explanation to do with piracy makes no sense because in the archaic period, there was no need for a secluded refuge, and later on, it would have been strategically suicidal to practise piracy next to the home port of the largest fleet in the Aegean, whose duties included suppressing piracy.

Nor is the interpretation of Phōrōn Limēn as a smuggler’s cove without problems. Chariton’s Chaereas and Callirhoē presents a revealing vignette of opportunistic smuggling, where the pirate Theron and his crew ponder where to offload and sell Callirhoē:

Ὡρμίσαντο δὴ καταντικρὺ τῆς Ἀττικῆς ὑπό τινα χηλήν· πηγὴ δ᾽ ἦν αὐτόθι πολλοῦ καὶ καθαροῦ νάματος καὶ λειμὼν εὐφυής. "Eνθα τὴν Καλλιρρόην προαγαγόντες φαιδρύνεσθαι καὶ ἀναπαύσασθαι κατὰ μικρὸν ἀπὸ τῆς θαλάσσης ἠξίωσαν, διασώζειν θέλοντες αὐτῆς τὸ κάλλος· μόνοι δὲ ἐβουλεύοντο ὅποι χρὴ τὸν στόλον ποιεῖσθαι. καί τις εἶπεν ‘Ἀθῆναι πλησίον, μεγάλη καὶ εὐδαίμων πόλις. Ἐκεῖ πλῆθος μὲν ἐμπόρων εὑρήσομεν, πλῆθος δὲ πλουσίων. Ὡσπερ γὰρ ἐν εὑρήσομεν, πλῆθος δὲ πλουσίων. ὥσπερ γὰρ ἐν ἀγορᾷ τοὺς ἄνδρας οὕτως ἐν Ἀθήναις τὰς πόλεις ἔστιν ἰδεῖν.’ ἐδόκει δὴ πᾶσι καταπλεῖν εἰς Ἀθήνας, οὐκ ἤρεσκε δὲ Θήρωνι τῆς πόλεως ἡ περιεργία· ‘μόνοι γὰρ ὑμεῖς οὐκ ἀκούετε τὴν πολυπραγμοσύνην τῶν Ἀθηναίων; δῆμός ἐστι λάλος καὶ φιλόδικος, ἐν δὲ τῷ λιμένι μυρίοι συκοφάνται πεύσονται τίνες ἐσμὲν καὶ πόθεν ταῦτα φέρομεν τὰ φορτία. ὑποψία καταλήψεται πονηρὰ τοὺς κακοήθεις. Ἄρειος πάγος εὐθὺς ἐκεῖ καὶ ἄρχοντες τυράννων βαρύτεροι. μᾶλλον Συρακουσίων Ἀθηναίους φοβηθῶμεν. χωρίον ἡμῖν ἐπιτήδειόν ἐστιν Ἰωνία, καὶ γὰρ πλοῦτος ἐκεῖ βασιλικὸς ἐκ τῆς μεγάλης Ἀσίας ἄνωθεν ἐπιρρέων καὶ ἄνθρωποι τρυφῶντες καὶ ἀπράγμονες· ἐλπίζω δέ τινας αὐτόθεν εὑρήσειν καὶ γνωρίμους.’ ὑδρευσάμενοι δὴ καὶ λαβόντες ἀπὸ τῶν παρουσῶν ὁλκάδων ἐπισιτισμὸν ἔπλεον εὐθὺ Μιλήτου, τριταῖοι δὲ κατήχθησαν εἰς ὅρμον ἀπέχοντα τῆς πόλεως σταδίους ὀγδοήκοντα, εὐφυέστατον εἰς ὑποδοχήν. "Eνθα δὴ Θήρων κώπας ἐκέλευσεν ἐκφέρειν καὶ μονὴν ποιεῖν τῇ Καλλιρόῃ καὶ πάντα παρέχειν εἰς τρυφήν. ταῦτα δὲ οὐκ ἐκ φιλανθρωπίας ἔπραττεν ἀλλ᾽ ἐκ φιλοκερδίας, ὡς ἔμπορος μᾶλλον ἢ λῃστής. αὐτὸς δὲ διέδραμεν εἰς ἄστυ παραλαβὼν δύο τῶν ἐπιτηδείων. εἶτα φανερῶς μὲν οὐκ ἐβουλεύετο ζητεῖν τὸν ὠνητὴν οὐδὲ περιβόητον τὸ πρᾶγμα ποιεῖν, κρύφα δὲ καὶ διὰ χειρὸς ἔσπευδε τὴν πρᾶσιν.

Ch. 1.11–12

Presently they anchored in the shelter of a headland across from Attica, where there was an ample spring of pure water and a pleasant meadow. Taking Callirhoē ashore, they told her to wash and to get a little rest from the voyage, wishing to preserve her beauty. When they were alone, they discussed where they should make for. One said, ‘Athens is nearby, a great and prosperous city. There we shall find lots of dealers and lots of the wealthy. In Athens, you can see as many communities as you can men in a marketplace.’ Sailing to Athens appealed to them all. But Theron did not like the inquisitive nature of the city. ‘Are you the only ones,’ he asked, ‘who have not heard what busybodies the Athenians are? They are a talkative lot and fond of litigation, and in the harbour, scores of troublemakers will ask who we are and where we got this cargo. The worst suspicions will fill their evil minds. The Areopagus is near at hand and their officials are sterner than tyrants. We should fear the Athenians more than the Syracusans. The proper place for us is Ionia, where royal riches flow in from all over Asia and people love luxury and ask no questions. Besides, I expect to find there some people I know.’ So, after taking on water and procuring provisions from merchant ships nearby, they sailed straight for Miletus and two days later moored in an anchorage seventy stades from the city, a perfect natural harbour. Theron then gave orders to stow the oars, to construct a shelter for Callirhoē, and provide everything for her comfort. This he did not out of compassion but from a desire for gain, more as a merchant than a pirate. He himself hurried to the town with two of his companions. Then, having no intention of seeking a buyer openly or of making his business the talk of the town, he tried to make a quick sale privately without intermediaries.

(Trans. by Goold, adapted.)

Although this novel is set in the Classical period, it is, a product of the Roman Imperial era. Yet as Bresson notes, the passage underscores some practical points that ought to be valid for Lakritos’ day.25 For one thing, Theron moors his galley (kelēs) seventy stades (about eight miles) from Miletos to avoid unwanted official attention; evidently, mooring close to Miletos would be to invite trouble, despite the fact that its officials tended not to ask awkward questions.26 Secondly, he avoids Attica altogether because of the Athenian reputation for nosiness and litigiousness, something corroborated by (and probably derived from) classical-era sources: Aristophanes jokes about this very reputation (Pax 505; Vesp. 764-1008; Nub. 207-208), and the Old Oligarch grouses about the reputation that the Athenians have among the elites of their empire for harassing them with lawsuits and for requiring allies to come to Athens and be judged by the demos ([Xen.] Ath. Pol. 1.14; 1.16-18; cf. Thuc. 1.77). We must also consider the state power of Athens. Recent research into the state capacity of ancient polities and empires has considered in detail how they projected power and imposed law and order within their borders.27 Athens’ fourth-century democracy would seem feeble indeed if an out-and-out smuggler’s cove existed within walking distance of Piraeus, its second-largest city. Thieves’ Harbour may have lain outside the boundaries of Piraeus and thus beyond the jurisdiction of its officials, but it did come under the purview of the local demarch. Besides, Athens yearly empanelled ten generals, one of whom was the ‘general for the countryside’, and they also appointed a peripolarchos whose duties included manning the various border forts and protecting the coastline against enemies.28 Since Athens was a direct democracy whose citizenry suffered financially if cargo ships skipped Piraeus and its customs officials and unloaded their cargoes tax-free a few miles along the coast, it would appear strange that, having the resources at hand, the Athenians did not stamp out this practice in short order.

One might also question the economics of smuggling from a would-be smuggler’s perspective. Smuggling goods into a specific area makes economic sense when certain items are unobtainable on the legal market or where the duty on imports is high. Evan Jones’ study of smuggling in sixteenth-century Bristol has shown how, rather than just being the habitual activity of a specific class of individuals, smuggling could also constitute a technique used by merchants to manage volatile market conditions and that under certain conditions legal trade might be more profitable. He notes, in particular, ‘specific’ taxes, viz. set taxes per commodity unit that were not calibrated to reflect a percentage of the commodity’s market value. Looking at Medieval wool price schedules, he notes that ‘at a given time, the price of English wool could range from £13 per sack (364 lbs) for the best ‘March’ wools to £2, 10s. per sack for the cheapest Sussex wools. This is important because it meant that the ‘specific’ duties on wool, typically £2 per sack, would have amounted to a 15 per cent tax on the most expensive wools but an 80 per cent tax on the cheapest varieties’.29 The situation seems to have been very different in Classical Attica, for we know of no imports that were explicitly banned by the state, and one wonders why anyone would take the risk of being caught simply to avoid the pentēkostē (2% ad valorem tax), especially when the pool of potential buyers (and thus the competition for the commodity in question and the attendant higher sale price) would be so much smaller than that at the legal market.30 In other words, any money saved by dodging the 2% tax could be lost in fencing the cargo illegally. The Athenians were less worried about smuggling into Attica than the opposite – the smuggling of critical commodities, above all, grain, out of Attica (Dem. 34.37; 35.50; 58.8-9). It does not mean that smuggling did not often occur, especially in out-of-the-way places, but the proximity of Thieves’ Harbour to Piraeus (and thus to busybodies, officials, and the navy) makes it an unlikely candidate as a smuggler’s cove.31

Above all, the idea of smuggling sits uncomfortably with what is described in the Against Lacritus. The fact that the speaker assumes that his audience has heard of Thieves’ Harbour shows that this was not some secret cove known just to smugglers but that everyone knew about it. Furthermore, his main point at §28 is that merchants can sail from this harbour to any destination at any time without officials noticing. Still, he says nothing about smuggling and does not claim that the Phaselites were trying to land cargo at Thieves’ Harbour. According to the actions that he describes, the Phaselites openly moored at Thieves’ Harbour for nearly a month; if Thieves’ Harbour were solely a smuggler’s cove, this behaviour would have been extremely risky. Instead, the Phaselites spent their time walking around (περιεπάτουν: [Dem.] 35.29) in the deigma (sample market), where merchants would mill about offering samples of their cargo to be tested for quality by prospective buyers, and purchases would be agreed for bulk sales based on the sample.32 Bresson notes an anecdote in Plutarch’s Life of Demosthenes (23.4) where grain merchants at the deigma carry around (περιφέρωσι) samples of their produce in a bowl; the verb περιεπάτουν at [Dem.] 35.29 could therefore potentially refer either to the Phaselites looking to sell or buy a cargo.33 It is perhaps too easily assumed that the Phaselites must have been looking to sell a cargo; but they could as easily have arrived under ballast with money to buy a cargo (cf. [Dem.] 35.25) – we simply do not know, and both possibilities should remain open. It is crucial to note that the speaker states explicitly that the Phaselites did not unload a cargo ([Dem.] 35.29-30); if by this statement he meant only ‘at the emporion’, it is strange that he makes no rhetorical capital about the possibility of smuggling. Nor should we suppose that clinching a deal at the deigma must necessarily have led to cargo being loaded or unloaded at Thieves’ Harbour. That is, of course, possible (Theron-style). But the Phaselites may have wished to keep their vessel out of sight for as long as possible. On this scenario, once they had struck a deal (either to buy or to sell a cargo) in the deigma, they could have entered Piraeus at dawn, concluded their business, and sailed away.

This explanation has the advantage of avoiding the awkward argument that the Phaselites were smugglers moored next to a huge centre of naval power for nearly a month. It also addresses an obvious difficulty that the Phaselites faced: they returned to Attica principally to do business in the deigma – Piraeus was, after all, the largest emporion in the Eastern Mediterranean. However, if they moored openly in Piraeus, news about their return on a different vessel than that on which they had departed would quickly have reached their creditor’s ears, and they would have instantly faced the headache of having to convince them that the shipwreck off Crimea was a valid reason for not repaying the loan.34 The prospect of a lengthy lawsuit was the last thing a merchant wanted, and it is exactly what the Phaselites got in the end (including Artemon’s brother Lakritos being dragged into the business and having to lodge a paragraphē against the indictment). Their behaviour, as described in the speech, fits far better the role of nervous debtors who are eager to do business at Piraeus but want to avoid a messy and potentially expensive lawsuit. They may well have lacked confidence that their case could be proven in court. Instead of assuming that the Phaselites had moored at Thieves’ Harbour to conduct some kind of smuggling side-hustle, it makes better sense to see this action as an attempt to keep the news of the shipwreck away from their creditors long enough to conclude their business in Piraeus before they found out and lodged an indictment.35

To explore further this possibility – and the vulnerabilities in Athens’ formal oversight of maritime trade – we must examine the role of intra-regional maritime trade along the Attic coastline. As we shall see, the Phaselites were in a good position to attempt such a ruse.

II. Attica’s Regional Harbours

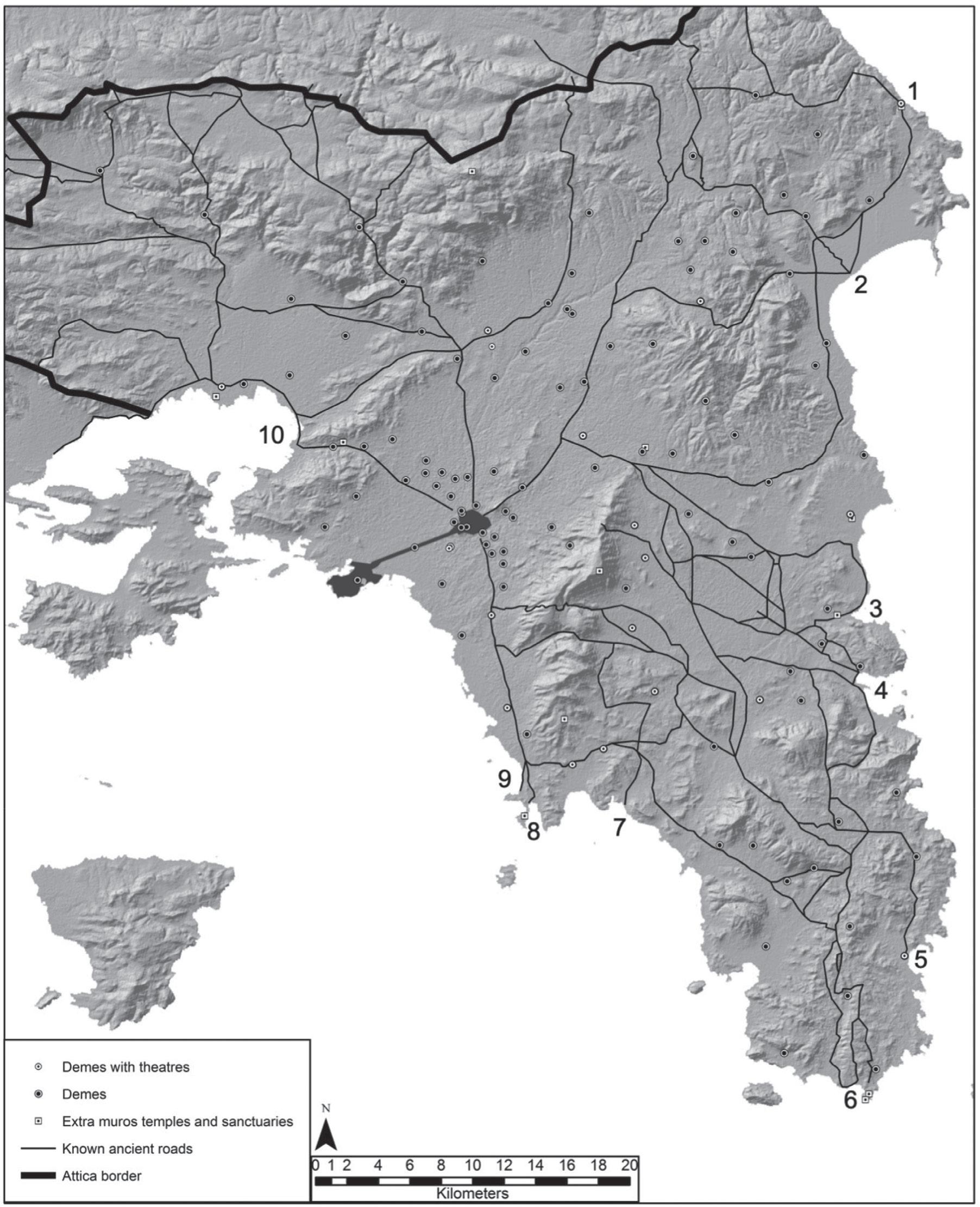

In enumerating Attica’s resources, Xenophon wrote that ‘just like the land, so too is the sea surrounding the countryside extremely productive’ (Vect. 1.3). Apart from the significance of fish to the Athenian diet, the role of local fishermen in meeting this demand, and the possibility of low-level shipbuilding industry and ferrying in certain demes,36 we must also consider the integration of agriculture and seafaring. As early as c. 700 BCE, Hesiod assumed that a prosperous farmer living close to the sea would own a boat and he advised his brother about how to ship off his agricultural surplus for sale (Op. 43-46; 622-632; 643-645; 671-672; 689-693; 805-809; 814-818).37 For Hesiod, overloading a boat is like overloading a cart; the parallelism gives equal weight to the two main technologies for transporting produce in bulk (Op. 689-693). Around the same time, Homer could imagine Odysseus’ holdings sprawling beyond Ithaca, with herds pastured on the adjacent mainland whose herders would transport fattened cows across to Ithaca by boat (Od. 20.185-190). There is no reason to suppose that a similar integration of agriculture and seafaring did not occur in Greece three or four centuries later. Indeed, Leidwanger has shown that this was true of the Roman Eastern Mediterranean.38 By the time of the Peloponnesian War, even the rugged interior of the Peloponnese was well integrated with maritime trade and the coastal economy through networks of roads and harbours (Thuc. 1.120.2). We know of specific cases of retailers who loaded baskets of fish onto shoulder-yokes at coastal locations like Epidauros and Argos and proceeded on foot towards markets in Arcadia (Arist. Rhet. 1365a26; SEG 42.293).39 A fortiori, this was all the more true of Attica, whose topography presented fewer logistical problems and whose coastline was dotted with several perfectly legitimate minor harbours used for intra-regional coastal trade, which included the relaying on of local Attic cargoes (esp. silver from the mines at Laurion, but also fish and agricultural products) to Piraeus and, conversely, the redistribution of goods either manufactured in the urban centre or imported into Piraeus via long-distance trade to consumers in the various Attic demes.40 It is also possible that this infrastructure facilitated the delivery of Attica’s products to merchants operating out of the emporion who had made bulk purchases based on samples tried at the deigma.41 A glance at a recent map (see Map II below) plotting known wagon roads in classical Attica shows that a number of these touched at or terminated in bays along the Attic coast, strong circumstantial evidence for the integration of agriculture and coastal trade.42 Looking clockwise, wagon roads link to: (1) Rhamnous, (2), Marathon Bay, (3) Brauron, (4) Porto Rafti,43 (5) Thorikos, (6) Sounion, (7) Agia Marina, (8) Vouliagmeni Bay, (9) Kavouri Bay, and (10) Eleusis Bay (including Skaramangas).

Map II: The road network of Attica. Image courtesy of Maeve McHugh.

Literary sources provide key evidence too. Pseudo-Scylax (Periplous §57) mentions no fewer than seven Attic harbours: one at Salamis, three at Piraeus, one at Anaphlystos, and two at Thorikos; and he also mentions that ‘there are many other harbours in Attica’. As Graham Shipley has pointed out, Pseudo-Scylax overlooks the harbour at Sounion and the double harbour at Rhamnous, though he mentions the forts at both these locations.44 We might also note the busy harbour at Oropos, a settlement that at times lay within, at other times outwith, Athenian control.45 It is worth noting that these local moorages or harbours were generally natural features: the Greek word limēn is not limited to artificial harbours in the modern sense; and these deme harbours will, of course, have been used in accordance with the rhythms of the wind and seasons.46

This ought not to be surprising, for local moorages and small wooden vessels played an important role in the movement of agricultural produce to market in many coastal parts of Greece until quite recently, though the post-WWII improvement of Greece’s road network and the increasing use of trucks significantly reduced the volume of such trade. Philip Betancourt’s ethnographical study of coastal trade around the Gulf of Mirabello in Eastern Crete has shown how Mochlos acted as the hub port for the gulf through which longer-distance traffic passed, whilst local fishermen and residents of the coast used smaller moorages to integrate their activities with such larger coastal towns.47 He notes that ‘the Union of Greek Shipowners recorded over 15,000 small sailing boats involved in coastal shipping in 1938, carrying over a million tons of goods annually (…) Because the official figure represents only the recorded cargo, one must assume it is very conservative’.48 Similarly, Leidwanger and Knappett note the resistance of Cypriot coastal traders, particularly carob traders, to British attempts to centralise the nodes of maritime distribution, preferring long-established patterns of trade that made use of numerous coastal bays.49 Even during the 1970s and into the 1980s, along the eastern shore of the Pagasitikos Gulf, smaller loads of agricultural produce were still sent from villages like Afisos and Lefokastro to the regional hub of Volos by boat, despite the region possessing a road network fit for truck transport (which dealt with bulkier loads).50 While the volume of trade in twentieth-century Greece and Cyprus obviously exceeded that of antiquity, the infrastructural patterns of trade show certain similarities.

What can we say about coastal traffic around ancient Attica? Already in the sixth century BCE, shepherds in the Vouliagmeni area were scratching onto the bare rock depictions of the ships of merchants plying the Attic coastline – local men whose names they knew, e.g., ‘the holkas of Egertios and Chariades’, and ‘the holkas of Diphilos’.51 We do not know where these vessels were constructed, but a century or more later, there was a flourishing shipbuilding industry in the vicinity of Piraeus.52 A passage from Xenophon’s Hellenica (5.1.23) provides a glimpse of the quotidian bustle of Attica’s coastal economy in the fourth century and the mixture of local coastal trade and longer-range external trade. When the Spartan commander Teleutias raided Piraeus in 388 BCE, he first captured the large merchant ships; then he cruised southwards to snap up the smaller fry plying the western Attic coastline: ‘he captured many fishing boats and ferryboats sailing in from the islands; and having come to Sounion he captured merchant ships, some full of grain, others of merchandise’.53 More can be said about Sounion, for an inscription dating to c. 460-450 BCE mentions the tolls paid by merchants using this harbour: if they carry a cargo weighing up to 1,000 talents (around 26 tonnes), they must pay a fee of seven obols; if they carry over 1,000 talents, they are to be charged a further seven obols per thousand talents (IG I3 8).54 These fees seem to have accrued to the cult of Poseidon at Sounion.55 Of course, Sounion could act both as a harbour for local intra-state trade and as a stop-off point for inter-state traders on the way from Piraeus to other more distant destinations or vice versa.

This overview of Attic coastal trade has a significant bearing on our interpretation of Thieves’ Harbour and the description of its use in [Dem.] 35.28-29. First, Thieves’ Harbour should be understood not as an isolated example of a non-emporion harbour in Attica, but as one of a string of local moorages that dotted the Attic coastline. Secondly, we must reckon with a general background of more-or-less constant coastal trade and fishing, differing in intensity throughout the year. In other words, the mooring of a small merchant vessel there need not have aroused any suspicions. This is key contextual information in understanding why the Phaselites moored there without official interference for nearly a month. But above all, the location of Thieves’ Harbour adjacent to Piraeus is crucial for understanding why it, and not some other coastal moorage, was the destination of the Phaselite merchants.

III. Vulnerabilities in Athens’ Oversight of Maritime Trade

We noted earlier that the Athenian state aimed to reap the benefits of foreign maritime trade, both in terms of its general economic benefits accrued to the citizenry, and the specific tax income levied at Piraeus. At the same time, the state did not wish to deprive its citizens of the infrastructural benefits of local coastal trade. Accordingly, it aimed at keeping the practitioners of these two tiers of trade separate. But this system was vulnerable to exploitation for two reasons.

First was the comparative lack – or in some cases complete absence – of state regulation of these local harbours and moorages, some of which, as we have already noted, were only used seasonally. Even a modern state, with all its sophisticated surveillance apparatus, cannot police all transactions in its territory; plenty of trade goes on under the radar, and this must have been all the truer of ancient states.56 Travelling peddlers traversing the Attic countryside like the Boiotian in Aristophanes’ Acharnians (860-958) had to pay a fee to enter foreign territory, but they did not have to worry about roaming agoranomoi when they tramped from farm to farm or village to village hawking their wares.57 Nor did fish-sellers who loaded their yoke-baskets with fish caught by fishermen from Attica’s coastal demes and proceeded inland to sell their wares to farmers (Antiphanes frr. 69 & 127 K-A; cf. Alciphron 1.1) have to worry about the intervention of the state. The Athenian state took a pragmatic approach, concentrating its regulatory oversight on the main nodes of market exchange, viz. Piraeus and the city agora, which were, at any rate, the best places to do business since they brought together many buyers, sellers, and a vast range of commodities.58 And indeed, this system was to no small degree a self-regulating one because of the basic incentives that foreign merchants faced. For a small 2% tax ad valorem, the merchant entering Piraeus could access the greatest number of potential buyers of his cargo in a tightly regulated environment whose institutions were designed to protect both buyers and sellers from fraud. As for coastal moorages beyond the emporion, regulation was less elaborate. We do know of some taxes (and exemptions from the same) imposed by the demes.59 Rhamnous is of particular interest: Bresson notes a tax raised from activity in the agora of Rhamnous (SEG 41.75),60 and we also know of one Athenian citizen who was granted ateleia tou plou by the Rhamnousians in relation to their harbours during the third century BCE (SEG 15.112). Blackman suggests an exemption from a local harbour tax,61 and the small docking fee known from Sounion (IG I3 8) provides a parallel. But in general, it is safer to assume uneven official oversight, which is precisely what the speaker says in the Against Lacritus (§28): ‘it is the same thing to moor in Thieves’ Harbour as it is if someone were to moor in Aegina or Megara, for anyone can sail out from that harbour to wherever he wishes and at any time he deems fit’.62 The point here is not that Aigina and Megara lack officials in their ports but that Thieves’ Harbour, like the ports of Aigina and Megara, was not policed at all by Athenian officials.63 For the Phaselites, Thieves’ Harbour presented several advantages over Piraeus. First, official oversight was much weaker. Secondly, as long as they did not try to unload cargo, they could moor there without interference indefinitely. But thirdly (and most importantly), Thieves’ Harbour was within reasonable walking distance of Piraeus, allowing the Phaselites to enjoy the best of both worlds: access to the biggest emporion of the Eastern Mediterranean, at whose deigma they could broker a deal (either as buyers, or sellers with a small portable sample), but also the advantage of maintaining a low profile and keeping their creditors in the dark for as long as possible.

A further vulnerability of this two-tier system of maritime trade was that there were not two distinct classes of vessels, one used for foreign trade, the other for local coastal trade. It would, of course, have been rather fishy if one of the larger merchantmen active in long-distance bulk trade (often large enough to carry cargoes of around 100-200 tons; some were even larger) sailed past Piraeus and anchored at Thieves’ Harbour – this could hardly have had an innocent explanation.64 But the situation was rather murkier for smaller vessels that might engage alternatively in interstate or intra-state trade. The speaker describes the crooked Phaselite merchants as using just such a vessel on their outbound voyage to the Crimea: this ship, skippered by Hyblesios, was an eikosoros, a twenty-oared merchant galley – an intermediary type between the sail-dependant ‘round ships’ used for trade and the oar-dependant ‘long ships’ used for military purposes ([Dem.] 35.18).65 This particular ship was large enough to be used for long-distance trade.66 Yet it could equally be pressed into service for intra-regional coastal trade, which is what the speaker claims that the ship was doing along the Crimean coast when it sank; at [Dem.] 35.31-32, he relates that the eikosoros was carrying salt fish and eighty amphoras of low-quality Coan wine for a farmer travelling in the boat from Pantikapaion to Theodosia, for the use of his farm labourers.67 This, we may note, was not illegal activity for a foreign trader, since Theodosia had been made an emporion by King Leukon.68 We do not know what sort of vessel the Phaselites were travelling aboard when they anchored at Thieves’ Harbour, but we do know that it was skippered by another Phaselite, and if it were of a similar class, then it might have as easily passed as a local coastal merchant as it could an interstate trader.69 And we might further note the speaker’s claim that Lakritos – who was a pupil of Isocrates and ran his own educational establishment at Athens ([Dem.] 35.15, 40-41) – had schooled his brothers there ([Dem.] 35.42). Artemon probably spoke Attic Greek like a local. In other words, the Phaselites moored at Thieves’ Harbour were well-equipped to fit in and maintain a low profile, all the while visiting the deigma for business and keeping the news of the shipwreck from the ears of their creditors.

Conclusion

It seems that the picaresque name of Thieves’ Harbour – whose origin may have any number of explanations and is at any rate unknowable today – has boxed-in modern scholars’ interpretation of [Dem.] 35.28-29 from the start, priming them to interpret the passage and the location itself in terms of smuggling. However, we have seen both how the sources provide no clear evidence of smuggling or piracy there, and that there are good practical reasons for explaining the actions of the Phaselites differently. The passage should therefore be read on its own terms without assuming smuggling (or piracy) based on the name Phōrōn Limēn. When we do so, what emerges is rather significant; for not only can we make better sense of the speech itself – the episode also sheds light both on chinks in the armour of Athens’ institutional oversight of maritime trade and on an underappreciated element of Attica’s economic infrastructure: its string of coastal moorages, whose role in the practical operation of the economy (particularly the agricultural economy) provides further evidence against the primitivist view that Attica’s farmers were isolated from markets.70