Α 13th-century Iranian vessel in the Benaki Islamic Collection

Abstract

The redisplay of the Benaki Museum's Islamic collection in its new premises in the Kerameikos area, within the historic centre of Athens, has brought to light a number of important pieces which were kept in storage for many years. One of these pieces is a double-spouted pouring vessel from Iran, datable to the early part of the 13th century, which was previously owned by Marina Lappa-Diomedes, a keen collector who donated her collection of Iranian ceramics to the museum shortly after its opening in 1931. From the 11 th century onwards Central Asian Turkic nomadic tribes, notably the Saljuqs, made their way into Islamic territories and rapidly gained control of a large area which included Iran, Iraq, Anatolia and parts of Syria. Political and military power shifted from the central authority of the Caliph to various local rulers. Until the start of the Mongol invasions in the 1220's a relatively peaceful environment allowed the arts to flourish in a number of urban centres which had become prosperous through trade, resulting in the manufacture of luxury objects for the new ruling class. This period coincides with one of the most important in the history of Islamic ceramics, which saw technological innovations and the introduction of a variety of decorative techniques ranging from simple white or monochrome wares to the so-called 'silhouette' wares, underglaze painted wares, those decorated with lustre colours and overglaze enamel wares known as minai. A significant factor in these changes was the improvement in the quality of the material as a result of the discovery in the 12th century of a type of artificial clay called fritware or stonepaste. In the process of imitating imported Chinese ceramics with their fine quality and translucency potters introduced a ceramic body constituted mainly of ground quartz with the addition of small quantities of white clay and potash and covered with a transparent alkaline glaze. This breakthrough by Iranian potters is recorded in a text dated A.H. 700 (A.D. 1301) by Abu'l Qasim Abdallah ibn Ali ibn Muhammad ibn Abu Tahir, a member of a famous family of potters from Kashan, the leading centre of ceramic production from the late Saljuq period. The pouring vessel has two feline-shaped handles and two bullhead-shaped spouts. The animals, probably leopards with spotted bodies and small rounded ears, turn their heads backwards and face in opposite directions. The body of the vessel, bulbous in form, is painted with black designs and covered with a transparent turquoise glaze that stops at the foot ring. The designs are vertical compositions of leaf motives intercepted by curving peacock feathers. The lower part is decorated with sketchy plant forms. Two bands of Persian inscriptions, en reserve on a black background, run around the rim and the lower body of the vessel. The interior of the vessel is decorated on the rim with another inscription band repeating the word Allah (God) in a stylised form on a turquoise ground. The remainder is covered with a transparent colourless glaze and painted on the bottom with a group of twelve fish. The rim and the spouts are highlighted in cobalt blue. The shape of the Benaki vessel, not unusual in Saljuq ceramics, has a precedent in a much plainer monochrome type of a slightly earlier date. The more elaborate form under discussion here survives mainly in lustre decorated and minai ware, which display variations in size and in the number of handles and spouts. Such vessels may perhaps have had a lid but too few examples survive to be certain. A comparable piece decorated with the same underglaze painted technique, which is less common, is preserved in the Louvre: the entire body is painted with free floral sprays and it lacks spouts. The shapes of 12th- and early 13th-century ceramics derive primarily from two sources -contemporary metalwork and Chinese ceramics. The form of the Benaki pouring vessel is not encountered in Islamic metalwork of the period: it is more reminiscent of Chinese Song ware and particularly of incense burners of gui form with very stylised animal-shaped handles, which ultimately follow a Chinese archaic bronze shape. From the 9th century onwards imported Chinese ceramics had an ongoing influence on Islamic ware, although they were rarely copied faithfully: potters were not satisfied with the simplicity of form and decoration of Chinese ware and consequently used colour, such as blue or turquoise, and added extra ornamentation, thus giving the pieces a distinct Islamic character. The individuality of this vessel lies in the shape of the handles which face outwards instead of inwards, as also commonly encountered in bullhead-shaped spouts. Both of these features can be traced to ancient Iranian forms, suggesting the survival of pre-Islamic traditions. However small figurai sculptures, usually in the form of animals or birds, very frequently embellish bronze objects, and since pottery and metalwork are closely related during this period this seems a more probable source. These figurines have a long tradition in Iran and Egypt in both the pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods; their purpose is not merely decorative and they have a practical use as handles, finials or knobs, as in the case of this vessel. The style of the painted decoration is not unusual at this time, especially in the composition of the vertical leaf motifs and the sketchy plant forms on the underside. On the basis of a group of pieces from the Nasser D. Khalili collection, the austerity of the design suggests a link with the so-called Gurgan style: a particulatly close resemblance can be found in the decoration of a bowl whose individual motifs display a similar aesthetic quality and which bears the same inscription en reserve on a black background. Of the two bands of Persian inscriptions only the top one is legible: '[O you whose will it is to hurt me for the years and months] Who are free from me and glad at my anguish You vowed not to break your promise again It is I who have caused this breach'. This is a Persian poem in the form of a ruba'i (quatrain), a popular verse type established in Iran by the end of the 10th century. Its subject is love or the agony of love, as here, and it could also be a metaphor for the love of God. The use of cursive script instead of the kufic which was the norm in early periods, and of the Persian language instead of Arabic, represents a change which is characteristic of the 12th and 13th century when literature and ceramic decoration were closely related. The group of painted fish is another feature which makes the decoration of the Benaki vessel unusual. The fish motif is not rare on Saljuq ceramics but their position on the base of the interior, as if swimming, is less common. The motif first appears on ceramics in the late 12th century and is later found on metalwork, where from the 14th century onwards it becomes very popular and acquires a symbolic meaning. The shape of the vessel suggests that its purpose was to contain and pour liquid, a theory which may well be reinforced by the decoration of swimming fish. The vessel proved to be of special interest for two reasons. When received for treatment it displayed certain forms of deterioration which were common to many of the objects in the Museum's Islamic collection. In addition the decisions as to the level of restoration proved to be particularly difficult in this case: our aim was to display the object in such a way that visitors would not be distracted by the restored areas but at the same time to observe principles of conservation based on respect for the object and for the potter who created it. The object had been treated twice in the past. It had been reassembled using an animal glue and filling the gaps with unbaked clay, while subsequent additions to the fills were made in plaster of Paris. Colour matching of the fills had resulted in extensive overpainting of the original. The inscriptions on the inner and outer sides of the rim had also been restored where missing. Finally the vase had an overall green appearance as a result of a yellowing varnish being applied to its entire surface. Superficial removal of the varnish with solvents revealed the exquisite turquoise colour of the glaze as well as the extent of mechanical damage, restoration and overpainting. The surface of the glaze presented extensive crazing and was worn and pitted in varying degrees. Encrustations covered or had penetrated the cracked and worn areas of the surface, rendering large parts of the inscriptions illegible. Further examination of the object indicated that the present conservation treatment would have to focus on the following: removing the old restorations (both to protect the object and for aesthetic reasons), freeing the surface and cracks of the glaze from the encrustations, setting off the surface of the object to achieve the optimum level for display and, finally, deciding on the level of restoration. The fills and joins were easily taken down by immersion in warm water. The vase comprised of 210 sherds. After being saturated with water, the sherds were immersed in a solution of 10% nitric acid in distilled water as the encrustations on the glaze and in the cracks could only be removed by chemical means. After intensive washing and drying the majority of the sherds took on a dull appearance due to the removal of the varnish and any remaining element of the encrustations. In order to overcome this, the sherds were consolidated by immersion in a solution of 15% Paraloid B67 (acrylic copolymer) in White Spirit. Paraloid B67 was chosen instead of Paraloid B72 because it is soluble in White Spirit and because a different solvent system to the one used for reassembling the sherds (i.e. acetone) was desirable. The combination of chemical cleaning and consolidation of the sherds was successful as the surface of the object was to a great extent restored and study of the vessel became feasible once the inscriptions were legible. Following reassembly large gaps were filled with white dental plaster, while minor losses on the inner and outer surfaces were filled with Fine Surface Polyfilla. The toning of the turquoise ground colour and the restoration of the known decorative patterns in black and blue were the stages which proved the most problematic. The policy of the Benaki Museum in this regard is not one of minimal intervention but rather to favour extensive restoration on the basis of the overall perception of an object (in terms of shape and colour) by a non-specialist. Visitors can easily be distracted by strong contrasts between the toning of the filled areas and of the original and they may end up focusing on the quality of the restoration rather than on the object itself. The same can happen when the decorative motifs are left unrestored. In accordance with this reasoning it was decided to imitate the turquoise ground colour and to restore the black and blue decorations where repeated so that the restored parts can all be discernible as such on close inspection, while not distracting the visitor's attention when observed from a distance.

Article Details

- How to Cite

-

Θεοφανοπούλου Ο., & Μωραΐτου Μ. (2018). Α 13th-century Iranian vessel in the Benaki Islamic Collection. Mouseio Benaki Journal, 4, 133–147. https://doi.org/10.12681/benaki.18259

- Issue

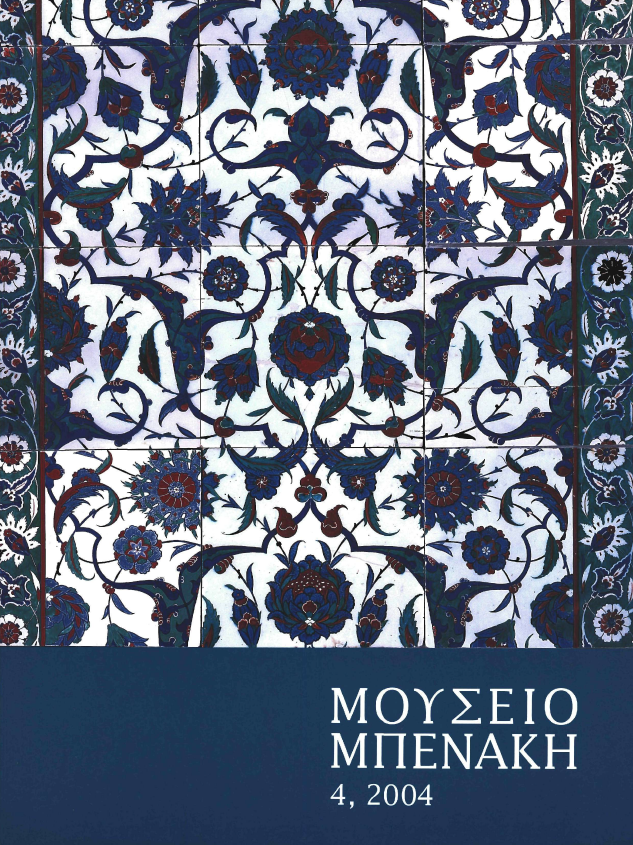

- Vol. 4 (2004)

- Section

- Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The copyright for articles published in Mouseio Benaki is retained by the author(s), with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles may be used freely for non-commercial uses, with the exception of the non-granted right to make derivative works, with proper reference to the author(s) and its first publication. The Benaki Museum retains the right to publish, reproduce, publicly display, distribute, and use articles published in Mouseio Benaki in any and all formats and media, either separately or as part of collective works, worldwide and for the full term of copyright. This includes, but is not limited to, the right to publish articles in an issue of Mouseio Benaki, copy and distribute individual reprints of the articles, authorize reproduction of articles in their entirety in another publication of the Benaki Museum, as well as authorize reproduction and distribution of articles or abstracts thereof by means of computerized retrieval systems.