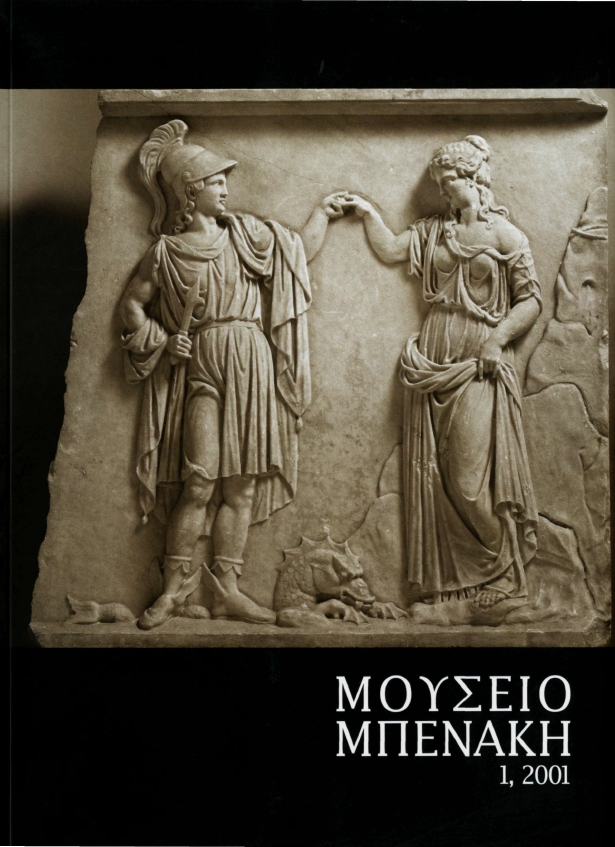

The Benaki Museum "Restoration of the Icons". Tradition and renewal in the work of a 16th century Cretan painter.*

Abstract

Among the works from the Helen Stathatos collection donated to the Benaki Museum is an icon of the Restoration of the Icons, which once bore a forged signature of Emmanuel Tzanfournaris; the icon was restored in 1996 by St. Stasinopoulos. The icon has two registers. The figures are arranged symmetrically around the vertical axis in the centre of the image, which is defined by the two icons placed one above the other, that of the Hodegetria above and of Christ the Great Hierarch below. The dominant Hodegetria icon is placed on an icon stand and supported by two young deacons in white sticharia and the oraria appropriate to their rank. Presiding at the ceremony beside them are Empress Theodora and Patriarch Methodios, holders of supreme temporal and spiritual office respectively, who were the protagonists in the final Restoration of the Holy Icons in 843. Methodios is attended by a priest and two monks, while next to Theodora is her young son Michael, with behind them three waiting-women. The lower register is densely populated with two rows of figures grouped around the icon of Christ the Great Hierarch and King of Kings. The first row consists of the confessors of Orthodoxy, three of whom hold scrolls with texts from the Synodikon of Orthodoxy and a canon which is sung on the Sunday of Orthodoxy. Behind them is a dense crowd of monks and lay figures, including three chanters. The stylistic features of the icon display affiliations with works of the Cretan school of the middle and the third quarter of the 16th century, such as the murals and portable icons of Theophanis and other anonymous contemporary works As is well known, the Restoration of the Icons is a subject found in only one surviving Byzantine icon, now in the British Museum, which dates from the end of the 14th century and probably comes from a Constantinopolitan workshop. The historical event of the Restoration of the Holy Icons in 843 does not seem to have resulted in the immediate creation of a specific iconographical type to crystallise iconolatry in pictorial form, but the British Museum icon indicates that this was in existence by the Palaiologan era. Moreover in the same period a similar composition showing public ceremonies - of veneration and procession - in honour of the Hodegetria made its appearance in Akathistos cycles in wall paintings and manuscripts. In the context of the troubled 14th century, when Byzantium was torn apart by dynastic strife and ecclesiastical disputes which involved the reassessment of the content of Orthodoxy and the role of the church, it is not impossible that this depiction of the Restoration was created to embody the expectation of renewed tranquillity within church and state, with the hoped-for conjunction of the two interdependent axes of power, Emperor and Patriarch, who dominate the upper register of this representation. From the iconographical point of view the Cretan artist has faithfully followed the British Museum icon, while making certain interesting variations and additions to the detail of his model. Among these is the inclusion of features which were widespread and especially popular in 16th century Cretan iconography, such as the portrayal of Christ the Great Hierarch and King of Kings. The addition of the inscribed scrolls which are not present in the Palaiologan work gives emphasis to the content of the scene, while lending the representation a didactic character which is found in other Cretan icons, mainly dating from the second half of the 16th century. Finally, the inclusion of additional figures - in particular, the densely populated second row in the lower register - endows the scene with an animation which is missing from the hieratic Palaiologan work. The result is that while the British Museum icon can be read mainly on two levels, as a commemoration of a historical event, the Restoration of the Holy Icons by Theodora in 843, and at the same time as a theological message of the triumph of Orthodoxy, here the innovations introduced by the Cretan artist project in dynamic fashion a much more down-to-earth and realistic element: the annual feast of icons on the Sunday of Orthodoxy. During the same period that the Benaki Museum icon was produced the subject of the Restoration appeared in wall paintings - for the first time, as far as I know - in major monasteries on the Greek mainland (Lavra and Stavronikita on Athos, Philanthropinon at Ioannina), and it became very popular on portable icons in the 16th and 17th centuries. This sudden appearance of the theme in the decoration of important monasteries may well be connected with contemporary theological events. As is well known the Reformation movement challenged the veneration of icons, and the Roman Catholic church responded with the Council of Trent (1545-63), which made express pronouncements on the significance of icons, with references to the Seventh Ecumenical Council, which the Catholics also consider part of their tradition and history. The official Orthodox church did not stand aloof from the theological disputes of the west, as we know, and both sides tried to win it over to their cause. It appears that Venetian occupied Crete was particularly involved in the theological debates of the day, and in such a climate it is not unreasonable to speculate that the intense arguments concerning the veneration of icons led to a renewal of interest in the Palaiologan iconographical type which constitutes a pictorial summary of the theme. An interesting pointer in this direction can be found in an icon of the Restoration of the Icons by Georgios Klontzas, now in Copenhagen, where that innovative painter uses as a model not the well known Palaiologan representation, but an engraving of the Council of Trent, a subject in wide circulation at the time. By this choice Klontzas made the reference in his icon to the contemporary theological debates even more apparent and comprehensible to the informed public of the era. If this theory is correct, the popularity of the subject of the Restoration in the 16th and 17th centuries is direct evidence for the living dialogue between post- Byzantine art and the burning theological questions of the age. Post-Byzantine Cretan artists drew from the rich iconographical armoury of the Byzantine tradition the thematology and the iconography which allowed them to reply opportunely and with dogmatic clarity to the theological questions which convulsed the era. At the same time, the variations which the Cretan artist introduced into this icon indicate how he enriched and recast his Palaiologan model and, in particular, they display his interest in including in the work elements of his social environment. This is evidence of a concern which is also found among other Cretan artists, mainly in the second half of the 16th century, a tendency to refashion the religious subjects they were depicting in order to create compositions more suited to the expression of their own personality and that of their times. * A shorter version of this paper was presented at the 8th International Conference of Cretological Studies (//' ΔιεδνέςΚρητολογικό Συνέδριο, Ηράκλειο 9-14Σεπτεμβρίου 1996. Περιλήψεις επιστημονικών ανακοινώσεων [Ηράκλειο 1996] 183).

Article Details

- How to Cite

-

Δρανδάκη Α. (2018). The Benaki Museum "Restoration of the Icons". Tradition and renewal in the work of a 16th century Cretan painter.*. Mouseio Benaki Journal, 1, 59–78. https://doi.org/10.12681/benaki.18328

- Issue

- Vol. 1 (2001)

- Section

- Articles

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The copyright for articles published in Mouseio Benaki is retained by the author(s), with first publication rights granted to the journal. By virtue of their appearance in this open access journal, articles may be used freely for non-commercial uses, with the exception of the non-granted right to make derivative works, with proper reference to the author(s) and its first publication. The Benaki Museum retains the right to publish, reproduce, publicly display, distribute, and use articles published in Mouseio Benaki in any and all formats and media, either separately or as part of collective works, worldwide and for the full term of copyright. This includes, but is not limited to, the right to publish articles in an issue of Mouseio Benaki, copy and distribute individual reprints of the articles, authorize reproduction of articles in their entirety in another publication of the Benaki Museum, as well as authorize reproduction and distribution of articles or abstracts thereof by means of computerized retrieval systems.